67: Why cake is important for product leaders

I’m writing about 100 things I’ve learned the hard way about product management. You can catch up on the previous entries if you like.

I have a patchy record of baking cakes.

In this article #

Right back when I first started, I’d look at the cake recipe as more of a guideline and then freestyle it. Unsurprisingly, my early cakes were complete rubbish.

As I went along, it began to dawn on me why the recipe’s method was telling me to do things in a particular way, and little by little, my cakes become increasingly edible. After some time, I realised that to achieve a decent result, I needed to have the right ingredients for the thing I was trying to make, in the right quantities. But even if I had the right ingredients in the right quantities, if I didn’t combine them the right way, say, by not creaming the butter and sugar together properly, I’d still not get a good result.

*crunching gear change*

This reminded me of how so many organisations seem to be trying to build their product culture these days.

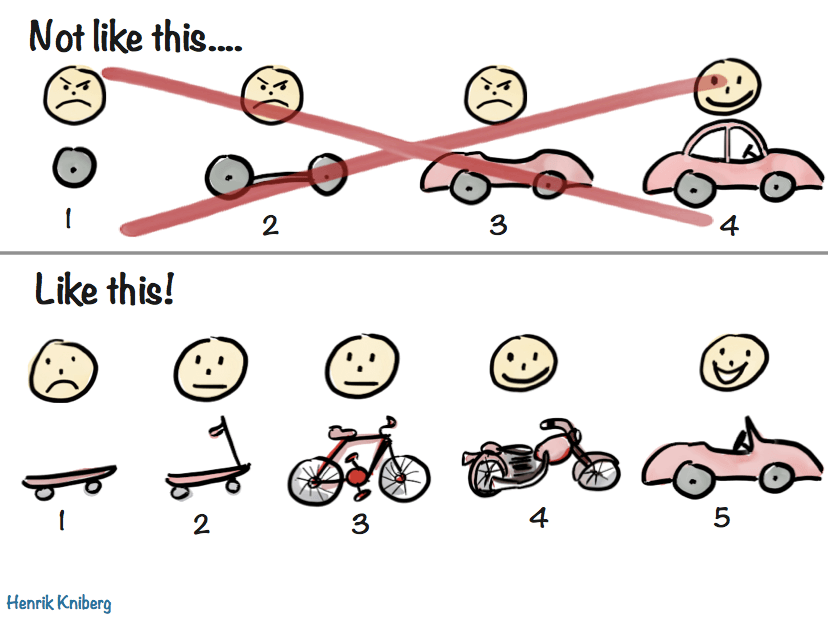

I see companies copying recipes from other organisations, but then freestyling their own attempt at it. They point to Henrik Kniberg’s description of Spotify’s engineering culture from back in 2014 or his description of iterative and incremental product development, and declare their product culture to be like that, seemingly without any real understanding of the concepts he describes.

These companies pick and choose their ingredients – a sprinkling of Agile here, a dash of communities of practice there – and throw them all into the mix. Even if they’re the right ingredients, they’re not in the right quantities, and certainly not being combined in the right way.

Worse are companies that then think a single, standard method is the key to success, regardless of the problem being solved. This is like trying to bake a Victoria Sponge and always starting with: “First, brown off the mince…”.

As I started to understand more about why I needed to combine my cake ingredients in the right quantities and in the right way, I gradually began to appreciate what was happening in the cake mixture. I could recognise when the mixture was too wet or dry, too runny or too thick, and how this would affect the baking time and temperature. I learned that it’s much easier and quicker to make two small cakes rather than one massive one. With a large cake, the cooking time seems to go up exponentially and the mixture never seems to cook evenly.

So we need to understand the reasoning behind the approaches we use to build a product culture. We need to appreciate what it is these techniques are actually trying to achieve and why, rather than simply aping them mindlessly. The presents us with a few increasingly difficult questions to answer:

1. What are the right ingredients?

Having autonomous, empowered multi-disciplinary teams is a good way to start. This means entrusting teams with control over their own way of working, toolchains and so on, but on the agreement that they’re jointly responsible for achieving the stated goal of the product.

Breaking down those organisational siloes and get product teams sitting together. If you’ve got all your developers sitting together in one place, your product managers all somewhere else, and so on, then it’s time for some desk moves.

Establishing true communities of practice to ensure that practitioners of each discipline in your organisation have a support network of peers, and can teach and learn from their peers. This is decidedly not the same as matrix management, which is more about doubling up on line managers who then tend to have conflicting sets of goals.

When I was working in GDS as head of the product and service manager communities, two of the earliest challenges to building a cross-government community were to coax out of hiding all the product people across dozens of government departments, and to enable a way for them to communicate reliably with each other. Some departments were locked down so tightly, they couldn’t even email out, let alone join a cross-government Slack channel.

Ensuring that product teams all have direct, frequent access to the users of their products, and that the teams are able to act immediately on the user feedback they gather.

Being able to measure how much you’ve been able to improve your user’s lives, or in other words, focus on user outcomes, not quantity of output.

All of John Cutler’s list, plus much, much more as the organisation’s product culture evolves.

2. What are the right quantities?

To start with, start small – get one product team right, then grow from there. All the while, product leaders need to continue to provide support and cover to avoid the team’s emerging culture being stifled by the prevailing (legacy) culture or, in some overly successful cases, from being buried under too many requests for work.

Then scale up, making extra efforts to increase visibility and awareness of what individual product teams are working on as you do. Weekly community get-togethers, as will working in the open will help to share information, encourage coordination between teams and hopefully avoid duplication of effort.

Open working can involve having regular ‘show the thing’ sessions, ensuring what the team is working on and their user research findings are highly visible on walls, blogging about what the team is doing and learning, making sure code repositories are open to all teams, and so on.

3. How should we combine those ingredients correctly?

This is the trickiest to answer because it entirely depends on the cake (read: product culture) you’re trying to bake. Each organisation’s set-up will vary, as will its people’s receptiveness to change in general, new concepts and ways of working. What works at one company won’t necessarily work at another, even if you copy it wholesale.

The biggest variable is always the people at your organisation. Inertia, fear of job obsolescence and defensive power-plays can all inhibit the rate of change. Once you understand the internal politics, who stands to gain or lose, you can start to determine the mix of ingredients you’re going to need and how they should be combined to not only change the organisation’s culture, but to make that change stick.

This is why it’s so important for product leaders need to have a range of techniques at their disposal, and the understanding of when it’s appropriate to use them.

Please feel free to start discussions below about this article, or to get baking tips.

Leave a Reply