71: The PMO strikes back

I’m writing about 100 things I’ve learned the hard way about product management. You can catch up on the previous entries if you like.

Sometimes I feel that each time product management practice evolves to empower and trust delivery teams more, there’s a corresponding response from the world of bureaucracy and red tape to re-establish oversight and enforce a rigid, one-size-fits-none process.

Okay, okay, so maybe likening the Project Management Office (PMO) to the Empire hunting down the Rebel Alliance is perhaps a teensy bit combative. But it’s how I feel sometimes. Just don’t let my desire for a weak pun give you the wrong impression. Let me explain.

In this article #

The best project managers are delivery managers

The best project managers I’ve worked with are the ones who have evolved from a role centred on controls, processes and documentation to one of trust, flexibility and coaching. These are the ones who now support and encourage the team to work in the way it needs to, rather than constraining it mindlessly to an unbending process.

Delivery managers, as typically used in the UK government’s digital teams, provide a perfect example of this kind of evolution.

Every product team should have a good delivery manager.

A lack of trust?

I see problems forming when I work with larger organisations that have an established and relatively powerful PMO, and which also want to modernise their approach to product management.

Typically all the organisation’s projects will be assessed, approved and managed by the PMO using their defined (and relatively static) processes. The problem I see is that the PMO enforces all these processes, controls, checkpoints, reports and hierarchy of authority because fundamentally the organisation does not trust the product teams to deliver efficiently and effectively.

I’m aware of that some of those mechanisms are ostensibly in place to communicate progress (or lack thereof) up the chain to allow corrective action to be taken. For me that’s just another way of saying that the product team isn’t trusted to communicate their own progress, solve their own problems or to ask for help when they need it.

That’s why empowering — and trusting — product teams to be autonomous and to decide for themselves how best to solve the problem at hand tends to set those teams at odds with the PMO.

Or an existential threat?

In an ideal world, we should be able to find ways to make best use of the body of expertise that sits within a PMO to help us evolve the way teams deliver products. However, more often than not, the desire to change how product teams work by freeing them from an overpowering process is seen as an existential threat by the PMO. This understandably creates a conflict that has to be resolved in some way by product and PMO leaders.

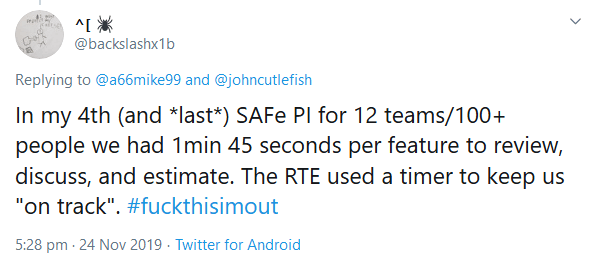

PMOs look upon the seeming chaos arising from autonomous product teams embracing ways of working with agility, freak out and immediately set about trying to regain control by reapplying the same old stage-gate process. Show me an organisation that claims to be ‘hybrid agile-waterfall’, ‘wagile’ (natch) or embracing SAFe (Scaled Agile Framework)1 and I’ll show you an organisation with a PMO desperately defending its existence against evolutionary change. SAFe is totally the PMO’s Death Star.

Product leaders need to defend their teams

As a bare minimum, product leaders need to defend their delivery teams from attempts to have working practices dictated to them dogmatically by the PMO. Only by entrusting the product team with the responsibility to deliver, and by ensuring they have a clear idea of the desired outcome, can we realistically expect them to do so. If we allow the team to be constrained by excessive process and documentation requirements, we shouldn’t be surprised by mediocre results.

A more collaborative approach would be to understand, for each of the PMO’s controls and processes, what the PMO is ultimately afraid might go wrong, and to demonstrate how the product team is already mitigating those risks.

For example, PMOs often require teams each week to compile laborious reports on progress. Lower-effort alternatives might be for the people most concerned about monitoring the team’s progress to attend daily stand-ups and sprint reviews, or to keep an eye on the team’s work-in-progress board (assuming the team is using some variant of Scrum and is good at working in the open), or to get a run-through of what the team has learnt or built that week.

Why tell people about progress in a report (that probably no-one ever actually reads) when you can show the progress to them in a tangible form?

This is one of the reasons I love ‘show the thing’ sessions so much.

Lead by example

Ever the optimist, I’d like to think that the most constructive approach would be to bring capable delivery managers into the organisation and have them demonstrate a better way of working to their project manager peers.

Then hopefully the PMO could choose to evolve into the entity the organisation needs it to become, rather than digging in its heels and trying to anchor the organisation in the past.

Here’s hoping, anyway.

Leave a Reply