73: You wouldn’t drive blindfolded – why you need user research

I’m writing about 100 things I’ve learned the hard way about product management. You can catch up on the previous entries if you like.

I heard a story of an octogenarian who drove himself to the hospital for his eye cataracts operation. (Just let that sink in a bit.) On his surprisingly safe return home, his relatives queried the sense of his actions. He replied that what he lacked in sight, he made up for in driving experience.

In this article #

Driving blindfolded

Imagine yourself jumping into your car, strapping in, and firing up the engine. You have a quick look around then pull on a blindfold before launching yourself into traffic. Likelihood of an accident? (Quite high.)

So why do so many take the exact same approach when it comes to creating products?

At best, organisations do a bit of research up front and no more, then set off on their journey to create the product – they might as well have a blindfold on.

At worst, there isn’t even any initial research: everything is either fed in from subject matter experts who ‘know’ the market so well, they don’t need to talk to users (a bit like our octogenarian above), or based on guesswork and assumptions. Sometimes product direction is even decided based on the revelation the boss had in the shower that morning.

It’s as if they’ve got the blindfold on before they’ve got out of the office. Goodness knows how they manage to find their metaphorical car.

How can this still be happening in this enlightened age of customer development and validated learning? I’ve seen organisations falling into a few common traps without realising.

Our subject matter expert knows EVERYTHING

In some organisations there are people who have built up plenty of experience working in a particular market or with a particular product and are considered subject matter experts. This person may also be the product manager, but this isn’t always the case.

It’s very easy to think you know what your customers need before you’ve actually spoken to them. In his book, Thinking, Fast and Slow, Professor of Behavioural Economics Daniel Kahneman described how you think in two different ways. One of these thinking systems is fast and instinctive – it causes you to jump naturally to conclusions and construct a plausible narrative around the available information – even if there’s not that much to go on.

When you see a tomato stalk out of the corner of your eye and think it’s a massive spider, that’s what your brain’s concluded from limited information. That’s also why it often feels okay to think we know what our customers want without any evidence to prove it.

The trick is to force your brain to engage the second thinking system – a slower, more analytical approach. This is how you think when you’re tasked to count the number of letter ‘e’s in this article – you can’t make an intuitive guess. This system takes more effort and happens to be lazy, letting the faster, instinctive system have the first crack of the whip.

If your subject matter experts actively refresh their knowledge by conducting frequent user research, then there’s no problem. Like the gentleman with the cataracts, it can however be tempting for them to rely on their accumulated experience without bothering to check whether things have in fact moved on recently.

This is an accident waiting to happen – hard evidence always beats intuition and prior experience.

We’ve spoken to our users

On face value, this doesn’t seem like a problem; speaking to your target market is important, right?

Well, it depends.

Being a spelling pedant, I remember being tremendously frustrated by someone making the case for their misspelling of a word by Googling all the other idiots who had made the same mistake.

It’s easy to introduce confirmation bias into the mix, where you only consider the evidence that supports your particular point of view. That there exists other overwhelming evidence to the contrary is conveniently ignored.

The other aspect of this is when people believe user research means asking users what they want the product to do, in effect asking them to design the product for you. As Marty Cagan, Steve Blank and others have described in detail, this doesn’t work because customers don’t know what’s possible, and they don’t know what they want until after they’ve seen it.

Yes, you need to talk to users; but early on, when you’re trying to figure out what they need, ask as many as you can find about how they tend to deal with certain situations. Common behaviours and problems will gradually emerge, and you’ll have a reasonable idea of the context for the problem.

There are numbers in a spreadsheet which MUST be true

The instant any predictions or assumptions are codified in a spreadsheet or equivalent, they suddenly take on an unjustified air of authority. This is sometimes known as the halo effect.

Calculating a complete guess to five decimal places doesn’t make it any more accurate. This is why I detest the common and misguided practice of hiding for several months in an airless office to write a massive business case document that will always fail to predict the future.

Unless you have a time machine or an accurate crystal ball, your time would be far better spent going and speaking with potential users to understand their problems and underlying needs, and let the business case emerge as you learn more about the value of the problem to be solved, and the potential cost of solving it.

You often see the same halo effect coming into play for any information that is in a slick report, presentation or coming from an expensive external source. Rather than taking it at face value, look at the evidence the information is based on and weigh up whether it’s trustworthy or not.

You don’t know what you don’t know

However you feel about former US Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, he gave the world this tongue-twisting quote:

“There are known knowns. These are things we know that we know.

“There are known unknowns. That is to say, there are things that we know we don’t know.

“But there are also unknown unknowns. There are things we don’t know we don’t know.”

Former US Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld

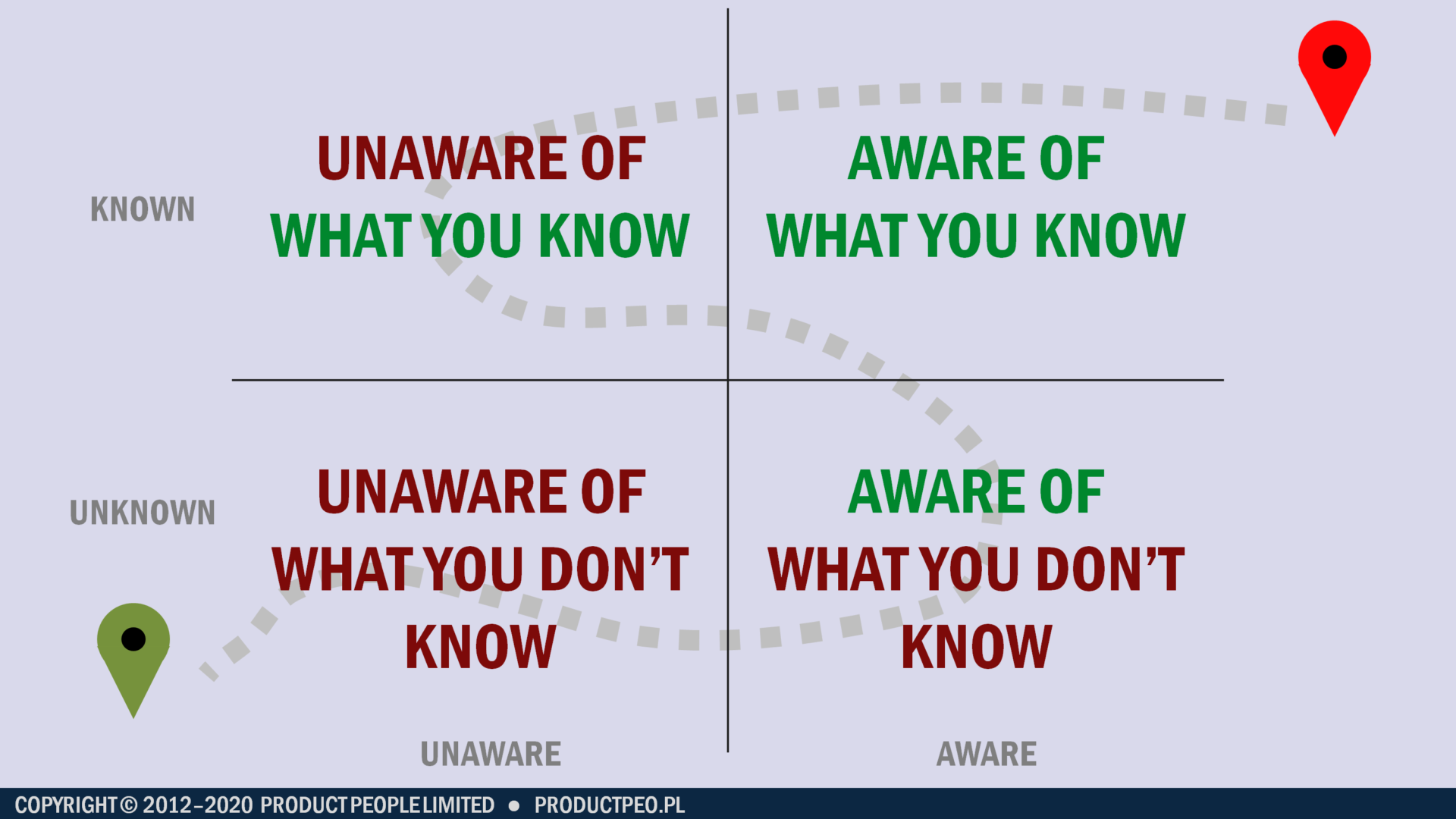

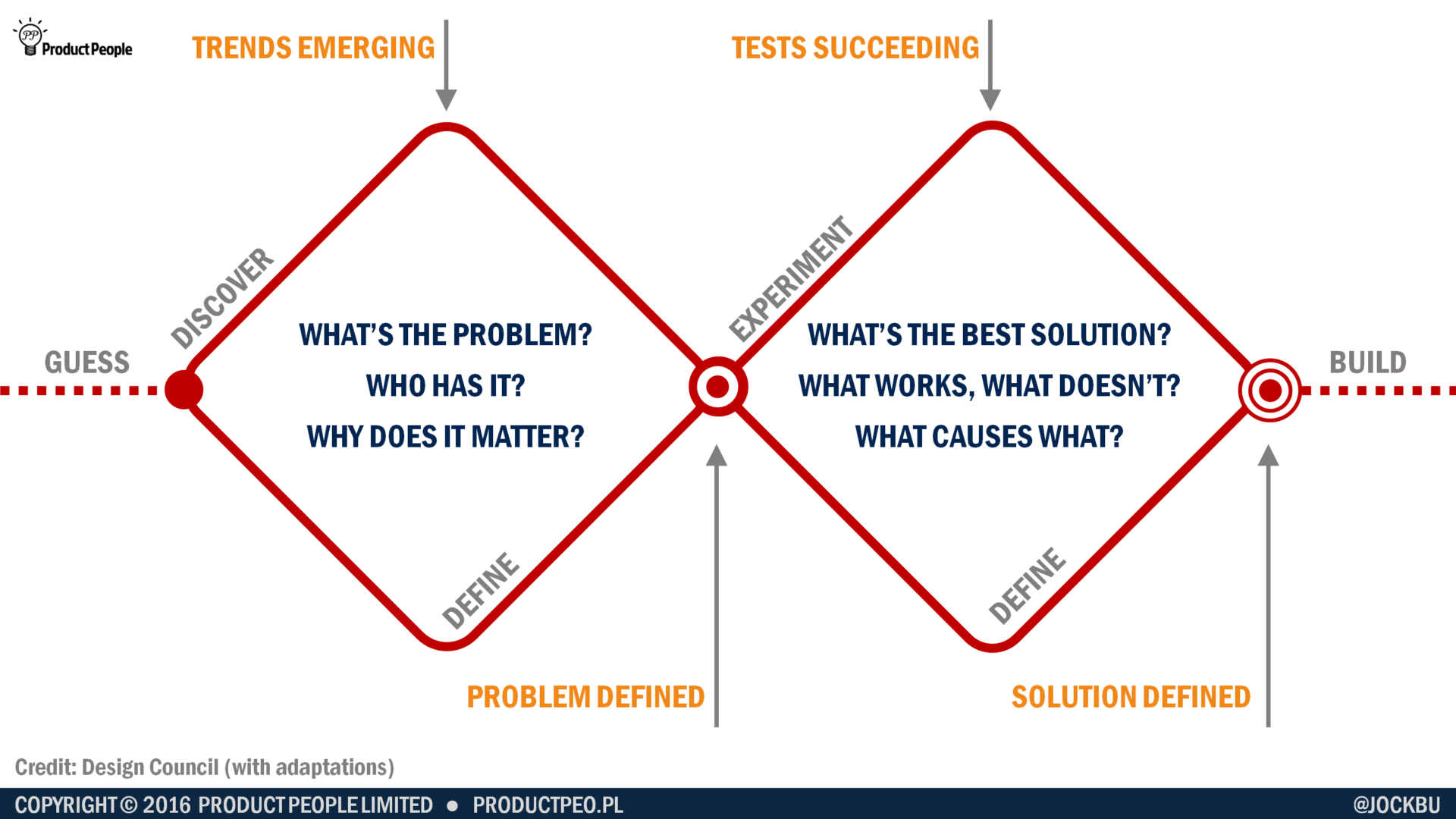

This pretty much maps out the path we take when going from the guesses and assumptions to knowledge and certainty.

You start out at the bottom-left of the grid. You might have some ideas, guesses or hunches about a problem you could solve, but you don’t really know anything, and there’s likely to be a whole bunch of things you haven’t even considered yet. In other words, you’re currently unaware of what you don’t know yet.

Then you do a bit of investigation and you start to realise there’s a bit more complexity to the problem and its solution than you’d thought initially. You’re becoming aware of what you don’t know, but at least you now know what are the right questions you should be asking.

So you do some more research and you come back with some results, but you’re not sure what story they’re telling you yet. This is when you’re unaware of what you know from the evidence you’ve gathered.

Then lastly you figure out what your evidence is telling you, it all stacks up and you can now say with a degree of confidence that you understand. You’re now aware of what you know.

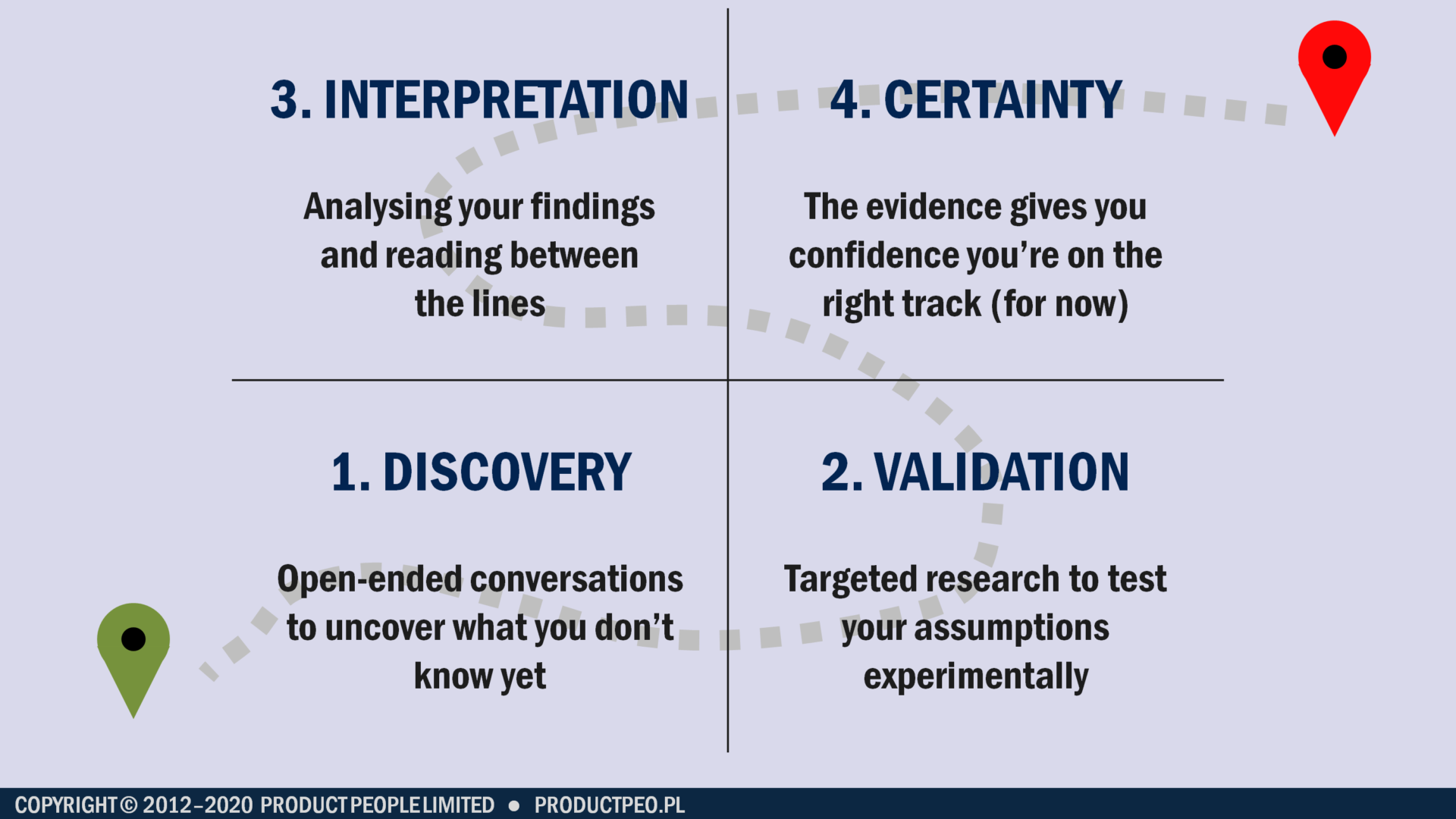

The path to knowledge and certainty in four steps:

- Discovery: open-ended conversations to uncover what you don’t know yet

- Validation: targeted research to test your assumptions experimentally

- Interpretation: analysing your findings and reading between the lines

- Certainty: The evidence gives you confidence you’re on the right track (for now)

Every answer prompts a dozen questions

This journey from guesses and assumptions to true knowledge is going to happen over and over for lots of different aspects of your product. To begin with, it will seem like every question you answer raises a dozen more questions. This is normal, and I’ve written a separate article that guides you through the process of discovery and validation without being overwhelmed.

Things to remember

Don’t let yourself be fooled into thinking you know things when you don’t – it’s just how your brain works. Force yourself to engage your analytical side to ensure you have hard evidence for what you believe to be the case.

Don’t assume that you or your subject matter experts know what your users need – speak to your users, but don’t ask them to design the product for you.

Don’t ascribe greater authority to information just because it’s typed up neatly in a report, or in a spreadsheet, or coming from an external consultant – assess the value of the information based on the evidence it’s based on, not the way it’s presented.

Final thoughts

The journey from guesses to certainty takes more effort, but is ultimately the only way to increase your chances of success with your product. Building your product based solely on hunches, guesswork or whatever your boss dreamt up in the shower that morning will have the same chances of success as trying to drive to work blindfolded.

Leave a Reply