75: The dirty little secrets of decision making

I’m writing about 100 things I’ve learned the hard way about product management. You can catch up on the previous entries if you like.

As individuals, we’re continually evaluating options and taking decisions. As product managers, we have the additional responsibility to balance the often competing needs of users, the business and wider ethical considerations. The decisions we make about our products have the potential to affect a much wider audience for better or worse, to a greater or lesser degree.

So I’ve been thinking about decision making. What makes one decision better than another?

In this article #

Every decision is a compromise

It is arguably extremely rare to encounter a clear-cut choice, in which there is an objectively correct option, with no associated downsides or compromises. Every decision we make requires us to trade off the possible positive and negative outcomes.

The assessment of whether a decision was a good one or a bad one depends on the perspective of the person assessing.

A totally selfish decision results in a broadly positive outcome for the selfish decision-maker, to the detriment of everyone else. There may be a downside for the selfish person if they’re aware of or care about the moral implications of their selfish decision. But let’s say they don’t care at all, so they see no negative outcomes from their decision. The decision was a ‘good’ one from the perspective of the selfish decision-maker, but not from everyone else.

A totally altruistic decision results in a broadly positive outcome for everyone else and usually has a downside for the decision-maker. The altruist may take some moral comfort from knowing their decision has benefited many others, but by definition they’ve lost out. The decision was a ‘good’ one from the perspective of everyone else, but not from the altruistic decision-maker.

Every decision we make sits somewhere on the spectrum from totally selfish to totally altruistic. Everything is a complex compromise where certain groups of people will benefit, others will not. As the adage by John Lydgate goes, you can’t please all of the people all of the time.

Short- or long-term effects?

Our decisions will also have different ramifications depending on what timescale you’re judging the effects. A quick win now could have nasty consequences in the long term – see all the technical and design debt in your product for details. Similarly, some short-term hardship might be necessary to reap the benefits later down the line.

The problem is that we have perfect hindsight, but no crystal ball. It’s easy to look back and point to something that turned out to be a crap idea. It’s much harder to spot it in advance. Shifting from internal combustion engines to electric motors will help to combat climate change, but it’s more difficult to predict the longer-term effects of increased mining for rare earth metals to make batteries.

We’re stuck with the decision we take

I find myself drawn to books, television and films with some kind of time travel plot device. I think it’s because I like the idea of seeing what would have happened if we’d taken different decisions. The problem is that we don’t have a time machine, so we only ever see the one outcome of each decision. We never get to see what could have happened, and we don’t get do-overs.

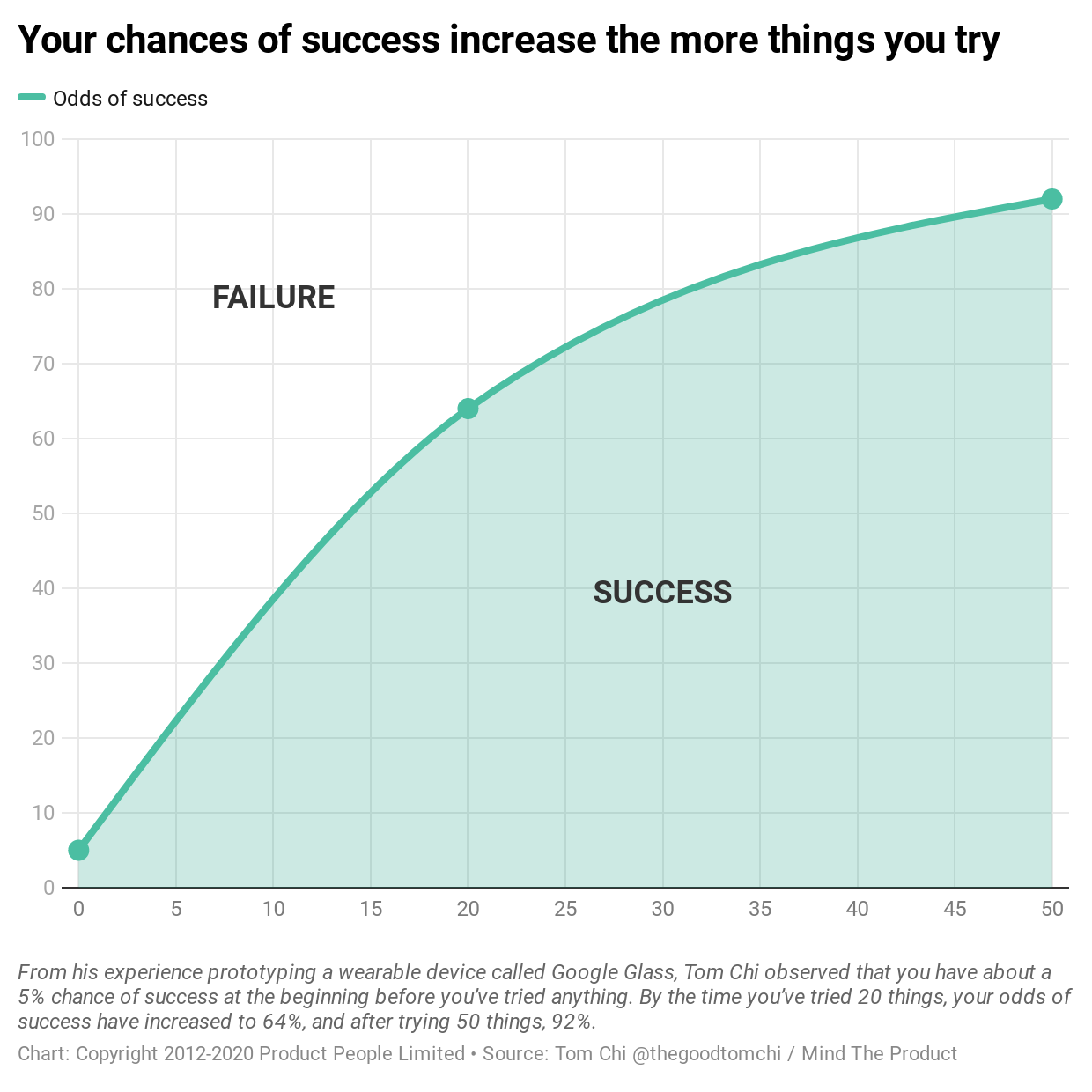

We can, however, do more to inform ourselves before we take the decision. I’m a big fan of quick, cheap prototypes and experiments to find out answers to questions about users and their problems. I love how Tom Chi described how your chances of success increase the more things you try.

From his experience prototyping a wearable device called Google Glass, he’d established that you have about a 5% chance of success at the beginning before you’ve tried anything. By the time you’ve tried 20 things, your odds of success have increased to 64%, and after trying 50 things, 92%.

Buridan’s Ass

While it may sometimes feel that ignoring a decision will make it go away, problems have a nasty tendency to increase in scope, depth and impact if left to fester.

It’s generally understood that taking any decision is better than failing to take any decision at all. The general reasoning goes that failing to take a decision deprives us of the opportunity to experience and learn.

Even a bad decision is not completely negative in outcome because you have, at the very least, learnt not to do that again should similar circumstances arise again. You will experience this effect if you ever decide to watch an Adam Sandler film.

There’s a philosophical paradox that places an equally hungry and thirsty donkey exactly midway between a bale of hay and a trough of water. Incapable of making a rational decision to move towards either, the donkey dies of hunger and thirst.

While the underlying paradox dates back to the Greek philosopher Aristotle, it was the French philosopher Jean Buridan who ended up being most closely associated with it. He was considering what would happen when an individual is faced with two equally (morally) good alternative courses of action:

Should two courses be judged equal, then the will cannot break the deadlock, all it can do is to suspend judgement until the circumstances change, and the right course of action is clear.

— Jean Buridan, c. 1340

Writers at the time helpfully satirised the concept with the equally hungry and thirsty donkey that came to be known as “Buridan’s Ass”.

Combating indecision

When faced with a difficult decision, indecision can set in. We might be fearful of the outcome of the decision, be faced with too many competing choices, or feel that we just don’t have enough information to make the best possible decision.

If you find yourself prevaricating over a decision, there are some techniques that can help you to move forward.

Call out your fears

It can be helpful to write down what you’re afraid might happen and see whether your fears have any validity. Another way of thinking about this is to ask yourself what’s the worst that could happen, then consider ways to mitigate it, allowing you to move forward with your decision.

Use predefined criteria as a filter

When faced with too many competing choices, like when you’re at an ice cream parlour and faced with dozens of flavours, it can help to set some specific and realistic criteria for your choice beforehand (”Must have chocolate in.”). This will make it easier to discard options and only have to choose from a smaller set. It’s also why having a clearly defined vision for your product makes it’s easier to filter out distractions from your product roadmap that will take you in the wrong direction.

Don’t worry about ‘best’ – ‘good enough’ is fine

If you’re stuck in a situation where you or your team never feel you have enough information on which to base a decision, it’s time to introduce the concept of ‘bounded rationality’. This is to accept that you’ll never have enough data to make the ‘best’ decision, and that if you keep gathering information you’ll never come to a decision. Instead, set a limit on the time and effort you’ll expend on research then decide on the alternative that meets some of your criteria, if not all, based on what you’ve discovered in that time.

I’ve found this approach particularly effective for breaking deadlock when my delivery team is split into factions, each proposing a different technology to solve a problem. I would give each faction a day or two to demonstrate how well their option meets some agreed criteria. This shifts the conversation from a debate about abstract notions of doing things ‘the right way’ to an objective assessment of what works best in the circumstances.

Making better decisions

We have different cognitive processes for making decisions and it’s important to force ourselves to use the right ones for making better decisions. It’s also important to recognise that there are no perfect outcomes to any decisions — everything is a compromise — so we have to make the best decision we can with the time and information available, and reconcile ourselves to live with the consequences of our decisions.

Further reading

“Empathy and Altruism: Are They Selfish?”, Neel Burton, Psychology Today, 12 October 2014 (retrieved 11 October 2020)

“The Challenge of Indecision”, Dale James Dwyer, Psychology Today, 25 April 2019 (retrieved 11 October 2020)

“Indecision is essential: Why we’re looking at our tough choices all wrong”, Susan Ewing, Salon, 19 October 2019 (retrieved 11 October 2020)

“Managing 3 Types of Bad Bosses”, Vineet Nayar, Harvard Business Review, 1 December 2014 (retrieved 11 October 2020)

“Indecision’s Impact on Your Happiness”, Brett Blumenthal, 19 March 2012 (retrieved 11 October 2020)

“Decision-Making”, Psychology Today (retrieved 11 October 2020)

“Buridan’s Ass”, Wikipedia (retrieved 11 October 2020)

Leave a Reply