87: An exercise in stakeholder alignment

I’m writing about 100 things I’ve learned the hard way about product management. You can catch up on the previous entries if you like.

One of the more uncomfortable scenarios I’ve spoken about before is when your stakeholders each have their own interpretations of the product strategy or broader corporate strategy. This lack of stakeholder alignment will cause you no end of problems.

In this article #

These may range from simple misunderstandings of what you’re doing and why, to outright opposition, because what you’re planning to deliver is not what they want.

As the product manager, you’ll be caught in the middle. For good reason, you can’t (or won’t) deliver what the stakeholder is demanding, but you can’t get anything done without that stakeholder’s buy-in and support. What to do?

Sometimes product managers mistakenly believe that their job is to achieve consensus. It’s not. Attempting to satisfy everyone’s needs, desires and points of view will lead to a muddled mess of an outcome that is at best mediocre, and at worst unsuitable for all.

PRODUCTHEAD: How to influence stakeholders

Given that it’s difficult to achieve consensus, we still need to be able to align stakeholders to a particular course of action — even if they don’t all agree with it.

Symptoms of misaligned stakeholders

You’ll know when your stakeholders aren’t aligned when they each think the company, and more specifically your product, should be doing something other than the stated current plan. And coincidentally, that ‘something’ just happens to benefit the stakeholder or their team. You get the idea.

Depending on the stakeholder’s style, they may assume you’re doing a laundry list of things that you’re not planning to. They may happen to mention these things to Very Important Customers who agree these are high priorities. They may happen to accidentally commit you to deliver these things in a deal which they’ve closed for a ton of commission revenue.

Another stakeholder approach I’ve seen is more overtly confrontational: they know you can’t proceed without their buy-in, so they use that as a negotiation tactic. It’s their way or no way.

Even if the misalignment is entirely innocent, it generates ‘noise’ for you. What stakeholders expect you’ll be delivering and what you’ll actually deliver in the product have diverged. Requests from different stakeholders will conflict with each other, or run counter to the product or corporate strategy. It’s a bit of a mess, really.

Don’t become known as “the profit prevention squad”

You could just say “no” and why to each stakeholder’s additional requests and deal with the fallout. This approach can work when your product strategy is super-clear and has the explicit support of the most influential stakeholders.

But more often than not, you simply end up becoming known as “uncooperative”, “not a team player”, or as the product team was called at one place I worked at, “the profit prevention squad”.

By saying no when everyone is misaligned in this way, you are treating the symptoms and catching the flak. It does nothing to unpick the underlying problem.

A practical approach to break the deadlock

I’d like to share with you one particular approach I’ve used in seemingly intractable situations like this. It’s an exercise you and the other product managers at your organisation can run with your key stakeholders.

A word of caution, however: just like any recommended tool or framework, it’s not going to work in all scenarios (see Your mileage may vary below).

The objective of the exercise is three-fold:

1. To surface all the extra stuff that’s currently not part of the plan to all the stakeholders. You will be making it clear that there are lots of additional requests, all competing for a scarce resource (product delivery).

2. To highlight the divergence across the group from what was the previously agreed strategy. This is to save you from becoming the proverbial messenger who gets shot.

3. To prioritise, filter and discard the additional requests from stakeholders. You’re going to do this in the context of the agreed list by getting the group to understand and make the trade-offs themselves. This is to save you from being the one that says “no” or “not now” to lots of stakeholders.

Running the exercise

The exercise goes something like this:

Preamble

Be clear on the reason why the session is necessary, and what the session seeks to achieve (stakeholder alignment on what will and won’t be done in the product*). The session is the stakeholders’ opportunity to advocate for the things they’re asking for over and above the agreed plan.

Get the list of agreed stuff up on a board. Gather the list of additional stuff from what you know about, and who’s asking for it. Solicit from the group of stakeholders any item additions or removals. Aggregate any items that are essentially the same request.

Stakeholders make their case

The stakeholder proposing each additional item briefly clarifies what each item is and why it’s needed in addition or instead of things on the agreed list.

Seek evidence for claims and note down statements such as “we’ll close 5 other deals if we add this thing”. You’re going to put these comments against people’s names in the meeting minutes for a bit of accountability.

Vote on business impact

The stakeholders (not the product managers — you’re deliberately remaining neutral) each cast dot votes on which of the additional items they anticipate will have the greatest positive impact on the business. You’re asking them to score only the additional items, not the ones that comprised the original plan.

Each stakeholder has a limited number of votes. They can distribute their votes as they wish (all on one, spread over several, or not vote at all). Note down the results and take photos.

Approximate effort

Next, if you can, the product managers should give an indication of high / medium / low development effort for the additional items. If there are too many, focus on the ones with the most votes. If the approximate effort for something is not known, assume it’s high until proven otherwise.

Prioritise the results

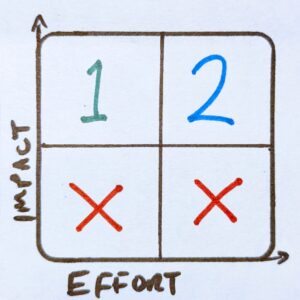

Rearrange the items into a 2×2 grid of impact versus effort. Prioritise the high impact / low effort, then the high impact / high effort, and discard the low impact items for now. Take photos again.

Explore the trade-offs

Ask the group to decide whether any of the highest priority additional items should displace items on what had been the agreed list. Everything must be a trade-off — you’re not going to magically squeeze in extra items for no additional effort, no matter how sweetly you’re asked to.

Be clear if an additional item would displace multiple items on the agreed list for whatever reason (greater relative complexity, items with dependencies).

Seek agreement

Seek explicit agreement on the new or unchanged list, and that anything not on that list is not part of the foreseeable plan.

* Caveat that the product managers may change the list if they learn something that fundamentally invalidates the assumptions for an item. This could be because there’s no evidence of opportunity after investigation, it’s technically impractical, a COVID-esque significant market shift occurs, and so on. But as you now have a prioritised list, you know what you’d pull in next were that to happen, and you would communicate any fundamental changes to the group.

Meeting minutes for accountability

Send round the minutes from the meeting, with photos and names against claims of future business, market need, evidence provided, and so on. Take the stance that the minutes are an accurate record unless challenged (i.e. speak now or forever hold your peace).

Possible outcomes of this exercise

Utter chaos

The stakeholders all argue with each other. If you’re lucky, a fist-fight might break out in the boardroom.

The stakeholders were never aligned, and you would have been caught in the middle, unable to succeed regardless of what you delivered on your product roadmap. All you can do is stick with the previously agreed list while they hash out their differences.

While frustrating, at least you’re not being blamed by all sides for being unable to square the circle. Reconvene when necessary to repeat or conclude the exercise. Bring popcorn.

Denial

Some stakeholders remain aggrieved that you’re not going to facilitate their pet projects. You should hopefully be able to combat any further back-channel requests from the stakeholders by referring them back to the agreed plan.

Grudging acceptance

Some stakeholders accept that you’re not going to deliver their requests any time soon and at least understand why.

Broader stakeholder alignment

The stakeholders have worked through their lack of alignment and everyone is clear on what’s (probably*) going to happen and why, and equally what’s not going to happen and why.

Ongoing communication

You’ll still need to reiterate the new agreed plan as you work your way through it. People can be very forgetful or have selective memories. Ahem.

If you and your fellow product managers are the ones doing the bulk of the communication, there will be less room for cross-talk and alternative interpretations among your stakeholders. Or at least, that’s what we’re hoping for, anyway.

Your mileage may vary

As with any product management advice that suggests following a particular recipe for success, please bear in mind a couple of things.

Firstly, there’s no guarantee this exercise will resolve all your stakeholder alignment issues. I’ve had varying results in different situations, and sometimes the dysfunction is simply outside of your control or influence.

Secondly, adapt and remix this exercise to suit your needs and your situation. For example, it’s all very well for me to suggest you get all your key stakeholders in a room together, but this may not be practical for you.

Final thoughts

What hopefully you have taken away from this article are the underlying principles — why you’re in the situation, why you need to tackle the causes not the symptoms, and a suggestion for how you can go about it.

What approaches have you tried when you’ve found yourself in a similar situation? Share your experience in the comments below.

Leave a Reply