89: What games taught me about customer onboarding

I’m writing about 100 things I’ve learned the hard way about product management. You can catch up on the previous entries if you like.

Video games aren’t necessarily everyone’s cup of tea, but some of the most successful games and products share a common attribute: they help the user become more skilled throughout their journey. Customer onboarding is a continual process.

In this article #

- Introduction

- Problems with typical customer onboarding

- Alternative approaches from games

- What can we learn about user onboarding?

- 1. The user’s first impression of your product is important

- 2. Playtest the hell out of it and ditch the parts that don’t work

- 3. Onboarding is really a continual process

- 4. Act like people are using your product because they want to, not because they have to

- 5. Don’t overexplain

- 6. Remember what users truly find rewarding

- Final thoughts

- Further reading

Problems with typical customer onboarding

A popular user onboarding approach with products at the moment is to provide some kind of in-app walkthrough for new users. This usually signposts key parts of the user interface and briefly explains what they’re for. In combination, new users will also typically receive a series of friendly emails highlighting some of the things they can try out.

More sophisticated approaches will trigger special emails when users do or don’t do certain things. These might include completing a particular significant task or if it’s been a while since the user last logged in. These approaches are all perfectly reasonable, and certainly better than not engaging with new users at all, but I find they tend to fall down in a couple of ways.

1. You clearly want me to use your product far more than I want or need to

I get it. It’s a competitive market and companies have to fight for people’s attention. But beyond that, companies seem to wildly overestimate how often and for how long people will use their product. Wishful thinking or over-promising to investors?

Let’s face it, the only product I wish to engage with for an extended period of time is my bed. For everything else, I have a specific task to complete as quickly as possible so I can get on with something else.

Similarly, it might be days or weeks between my uses of the product. What I don’t need is a series of increasingly panicked — and almost always automated — emails from “Jerry” saying they miss me and checking I’m okay. I get it. It would really help your MAU (monthly active users) numbers if I just logged in again. Thank you for your faux concern, “Jerry”. Unsubscribe.

2. It’s all changed. Again.

On my return to an app after a lengthy gap, I’ll admit I sometimes need a gentle reminder of how it works. These days however, this is less often due to my sieve-like memory, and more to the several major product redesigns in the intervening period.

I used to use Descript on a weekly basis for editing a video podcast. Even with that usage frequency, it still seemed to change fundamentally every time I opened the app. My routine had to evolve to allow for the obligatory 30-minute download and update process that preceded any actual editing.

Recently I returned to Descript after a few months away, and it was borderline unrecognisable. I just didn’t have the energy to figure it all out yet again. Now I’m all for rapid iteration and improvement, but with each update I lost all my accumulated muscle memory and had to re-learn the app from scratch. I couldn’t have been the only user struggling to keep up, could I?

If you’re going to force users to start over practically every time they use your product, it becomes more and more attractive for them simply to start over with an alternative product that changes less often.

Alternative approaches from games

You might think that video games have it easier with user engagement than your typical office productivity tool. I don’t think that’s in fact the case.

If I have a task to do, even if the product I have to use is glitchy and painful to work with, I’ll muddle through with it because I still have to do the task in question. With a game, I don’t have to do anything — I’m playing mainly for the enjoyment and possibly the bijou hit of dopamine for completing something in-game.

For that reason — playing is optional — if a game is too hard, too easy, or just unenjoyable, I’ll stop playing. And there’s going to be very little that would entice me back again.

The most successful game producers realise this and work very hard on several aspects of the game mechanic to keep players coming back.

Initial onboarding happens in-game

The most successful games tend to incorporate the onboarding process into the story being told. In Guerilla Games’s Horizon Zero Dawn (2017) your first actions are to help the game’s protagonist, Aloy, to explore an unfamiliar environment and learn some new skills along the way. By helping her to learn, the player is also learning the basic game controls.

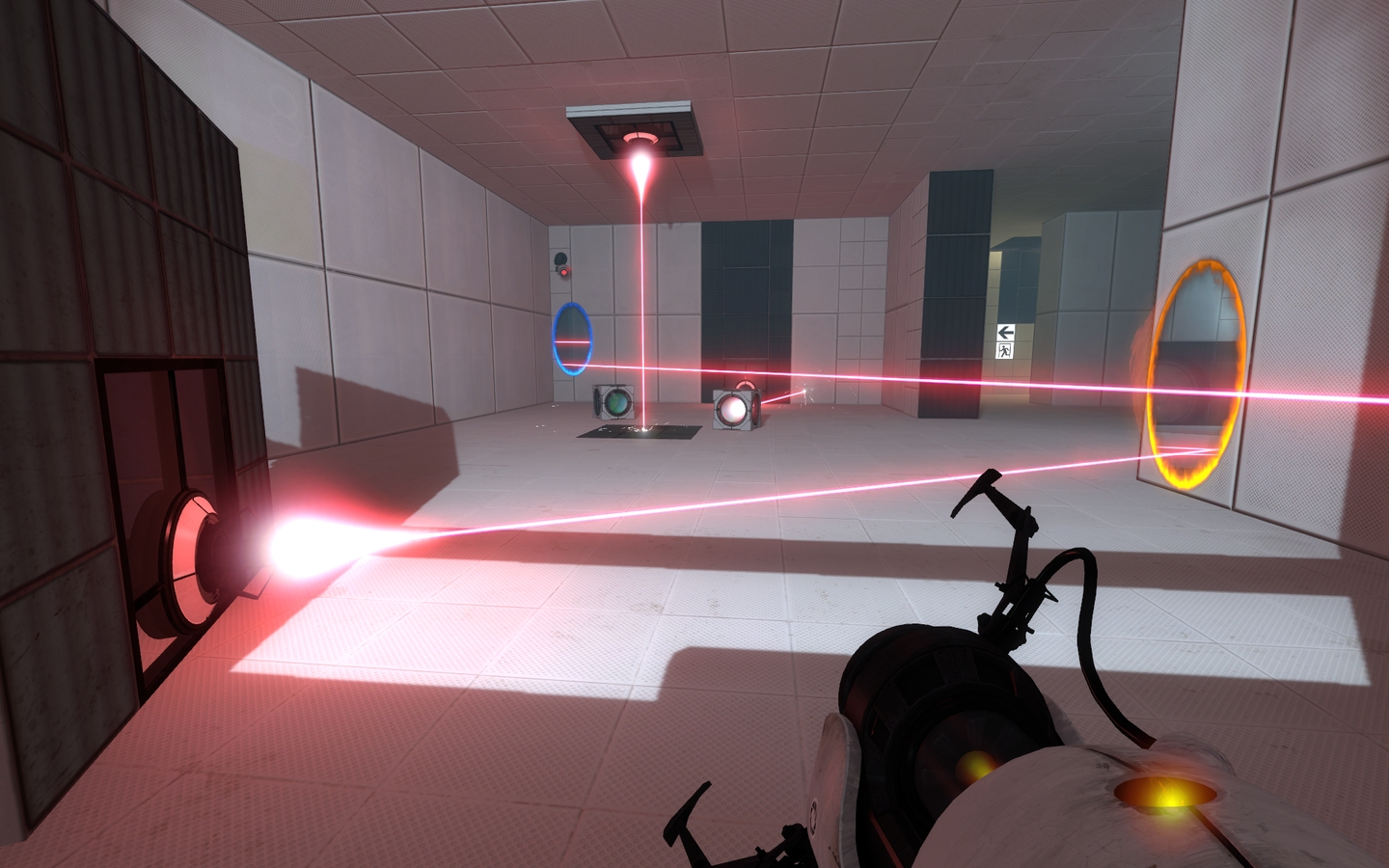

Valve’s Portal 2 (2011) introduction uses dark humour both to parody other games’ onboarding sequences and to teach how to play the game, all in the context of an action set-piece which quickly sets the scene and rewards the player’s progress.

At no point in these or many other game titles is the player’s immersive experience interrupted. You and each game’s protagonist are thrown together into the inciting events of the story, and only by learning together does the narrative progress.

The game is continually teaching players new skills

Part of the pleasure of playing a game is the gradual and comparatively frictionless it is for the player to acquire new skills. In order to progress through the game and reach the conclusion of the storyline, a player has to become more accomplished.

The game introduces new techniques to the player organically throughout the story. The player is shown how to do something, sometimes by an in-game character. The player then has a chance to practice, until some plot device occurs that hinges on the player’s ability to use that new skill competently and repeatedly, to reinforce the lesson.

This cycle of introduction, practice, reinforcement, and then combination with other techniques, means that the player become skilful enough over time to complete the game. Should the player then wish to play through the game again, they are often offered a much harder setting to present enough challenge to offset their greater skill.

An adaptive balance of challenge and reward

The process of acquiring new skills and making progress during the game is not strictly linear. Without the right blend of challenge and reward, players can be put off. Too difficult, and they give up. Too easy, and it dampens that little dopamine hit associated with achievement.

Consequently, game designers allow the game to adapt its difficulty dynamically based on the player’s ability in that session. If a player is flying through with ease, the game subtly makes things just a little harder. Similarly, if a player is repeatedly falling at the same hurdle, the game imperceptibly lowers the bar just a little for the player to stave off their frustration, regain their confidence and resume making progress.

Done well, the player almost never notices it happening. And as an interesting side-effect, this adaptive difficulty means each player’s experience of the game is entirely unique. It’s the ultimate personalisation.

What can we learn about user onboarding?

1. The user’s first impression of your product is important

If your users feel your product is not going to help them with their task, or will be too demanding to use, they’re going to choose another product.

Many games designer take extra effort to ease a new player into the game while it is the most unfamiliar to them. In the same way, the user’s first interactions with your product’s are critical to get right.

Early on, the user needs to verify that your product will enable them to achieve their primary task, and to gain the confidence that they are sufficiently skilled to be able to do so relatively easily.

2. Playtest the hell out of it and ditch the parts that don’t work

The user’s initial experiences with your product will strongly influence whether they keep using it, but you can’t drop the ball once they’ve become more invested.

A game that’s glitchy, annoying, not enjoyable to play, or fails to elicit an emotional reaction is a game that players can’t or won’t play. Game playtesters don’t simply help the publisher find game-breaking bugs, they also provide valuable feedback on aspects throughout the game that are too hard, too easy, too repetitive, as well as evaluating whether the overall story hits the right notes.

Test your product over and over, with lots and lots of users, novice and experienced alike. If some aspect of your product simply isn’t working for large swathes of real users, you’re going to have to change it or ditch it entirely. It’s not going to magically improve at launch.

3. Onboarding is really a continual process

If you can help your users to become increasingly confident with your product, and to achieve more satisfyingly complex results, you will encourage them to stick with your product for the long term.

Onboarding doesn’t end after the user’s first few interactions. As with games, your product should be progressively helping the user to learn relevant and helpful new skills at their own pace. If your product can help users to become more efficient at a few of the tasks they perform most often, they will see a real boost to their productivity.

As with games, when a user is ready to learn something new, teach them a technique, reinforce it through practice, then help the user to combine it with other techniques to perform more complicated tasks.

4. Act like people are using your product because they want to, not because they have to

Always assume that users have a choice — even if your product is the only one they can use (which is rarely the case), users can always choose not to use any product at all. They’ll either do the task manually, or not bother in the first place.

By adopting this mindset, you’ll become far more alert to the minor annoyances, difficulties and ambiguities in your product that you otherwise may be tempted to let slide. “Quality of life” improvements to your product are always worthwhile.

Even if you want to keep a new feature rudimentary to reduce development time, give it just enough polish to ensure it will help the user to succeed in their task with minimal friction.

5. Don’t overexplain

Unless you can be certain that telling genuinely adds value for your users, don’t. Show them instead.

As with most forms of entertainment, games prefer showing over telling. It helps to keep the player immersed in the game. But when a game player seems lost, this can trigger in-game dialogue or clues to help them get back on track. Games use this mechanic sparingly, because it can easily remove the challenge entirely, becomes annoying when deployed too often and ultimately breaks the immersion.

If you find yourself having to explain things to users at length in videos, in-app tooltips, emails or documentation (that nobody will read), then your product is failing to show users what they need to do.

6. Remember what users truly find rewarding

A user’s ultimate reward is to complete their task or achieve their goal quickly and easily, then move on to something else. Everything else is a distraction.

In games, the ultimate goal of the player is to complete the game or attain the highest level of skill. Even though side quests can be enjoyable, challenging and enriching in their own way, they are intentional digressions and the player almost always has the option to ignore them completely.

Products that have been ‘gamified’ often resort to giving users badges, trophies and other awards for completing certain activities. However, these activities are often distractions from the user’s main goal, and can often feel more aligned with the interests of the product’s creator than the user.

Winning a badge for filling out your user profile more completely, or referring the product to friends without any tangible remuneration other than a cutesy trophy are both examples of fake rewards. They benefit the company making the product, but provide no real value to the user.

By all means, award badges and suchlike as mementos as helpful reminders of the user’s own progress and acquisition of skill. But even if they confer bragging rights over the user’s peers, they hold little intrinsic value. The real achievement is what the product has enabled the user to do or create.

Final thoughts

At their heart, the best games seek to provide their players with entertainment, enjoyment and achievement. Why should your product be any different?

Further reading

“Onboarding 101: Lessons from Game Design”, Santiago Alonso, Medium, (23 January 2017, retrieved 22 April 2023)

“3 fundamental user onboarding lessons from classic Nintendo games”, Jackson Noel, Appcues blog (2016, retrieved 22 April 2023)

“Games UX: Building the right onboarding experience”, Léo Brouard, UX Collective (11 November 2021, retrieved 22 April 2023)

“Design better user flows by learning from proven products”, Pageflows

Leave a Reply