90: Always have a plan B

I’m writing about 100 things I’ve learned the hard way about product management. You can catch up on the previous entries if you like.

Have you ever wondered why product managers say “it depends” quite so often?

In this article #

It’s all a bit complicated

The best product managers I’ve observed continually weigh up the impact of many different shifting factors, and know what they will do next as a result. When considering what to do next with their product, they could be thinking about the likely net outcome of any or all of the following things all together:

How quickly can the delivery team fix a nasty bug that’s affecting customers? What if they can’t?

How would that timescale shift if one of the more capable developers were to postpone their annual leave? How likely is that to happen?

How receptive would the senior stakeholder be to accepting a delay to release?

What if the team were to swap out the buggy component for an alternative? How much time would be needed? Would it be technically feasible in the first place? Would doing so just introduce new and different problems?

How much would each course of action affect users positively and negatively?

How much would each course of action affect the business positively and negatively?

The product manager will be re-evaluating these probability calculations in their mind, possibly explaining why their brow always looks so furrowed. But to the outsider who’s unaware of this complex web of factors, the decision-making process will look rather opaque.

It may seem to them that the product manager is prone to changing their mind. Rather, what’s happening is that the product manager is noting changes in one more more of the factors that contribute to their decision, and that shift has been sufficient to nudge their chosen course of action. The goal is to achieve the best possible compromise given the circumstances.

Or it may seem to them that the product manager is ignoring an obvious course of action, when in reality, the product manager has considered and discounted it as an option, because there’s a bunch of hidden downside associated with it. Pulling on one thread could cause the whole thing to unravel in less than obvious ways.

So it’s no wonder our favourite response to a question is “it depends”. It really does.

Always have a plan B

[Q] Now, pay attention 007. I’ve always tried to teach you two things. First, never let them see you bleed.

[JAMES BOND] And the second?

[Q] Always have an escape plan.

The World Is Not Enough (1999), Danjaq / Eon Productions / MGM / United Artists

When I’m thinking about a course of action, I’m really asking myself a couple of questions:

How likely is this thing to happen?

What would I do differently if this thing happened?

Really what I’m doing is formulating my plan B (and C and D and so on). But I can’t plan for every eventuality, so I also need to consider the likelihood of needing to use that alternate plan.

I recently had to deliver some training remotely whilst away from my usual studio. My biggest concern was that the internet connection there would be too slow or unreliable to livestream my training.

I asked myself what if that turned out to be the case. What would I do differently? So I made sure I had a plan B in the form of a personal wi-fi hotspot with plenty of data allowance. From tests I conducted beforehand, I knew that there might be a drop in the quality of the streamed video, but it wouldn’t be that noticeable when streaming slides for the most part.

And of course I turned up to the venue on the day and found they had given me duff login details, so out came the wi-fi hotspot, and off I went.

You can’t plan for every eventuality

While I think it’s tremendously important for product managers to be considering what their plan B / C / D would be if something critical came up, not everything can be anticipated. Nobody could have predicted the COVID-19 pandemic, for example. However, the businesses that weathered it best were the ones who were able to formulate and execute a workable plan B quickly, then improve it as they went along.

It is important to ask “what if?” to explore possible scenarios, but some factors are more critical than others. In the case of my remote training delivery, if I didn’t have a decent internet connection, there would be no training at all, so all my other concerns and what-ifs were secondary.

Are you able to figure out the most critical factor that will affect your decision?

Don’t put it off — embrace it and practice

When we have a sense that something is going to be tricky or problematic, we may also have a tendency to put it off until later because it’s uncomfortable to deal with now. Some people will bury their head in the sand and hope it goes away. (It won’t.) Instead, hope for the best, and plan for the worst.

There are two useful analogies, one for making unlikely events mundane, and the other for orchestrating a complex series of events more easily.

Making unlikely but critical events mundane

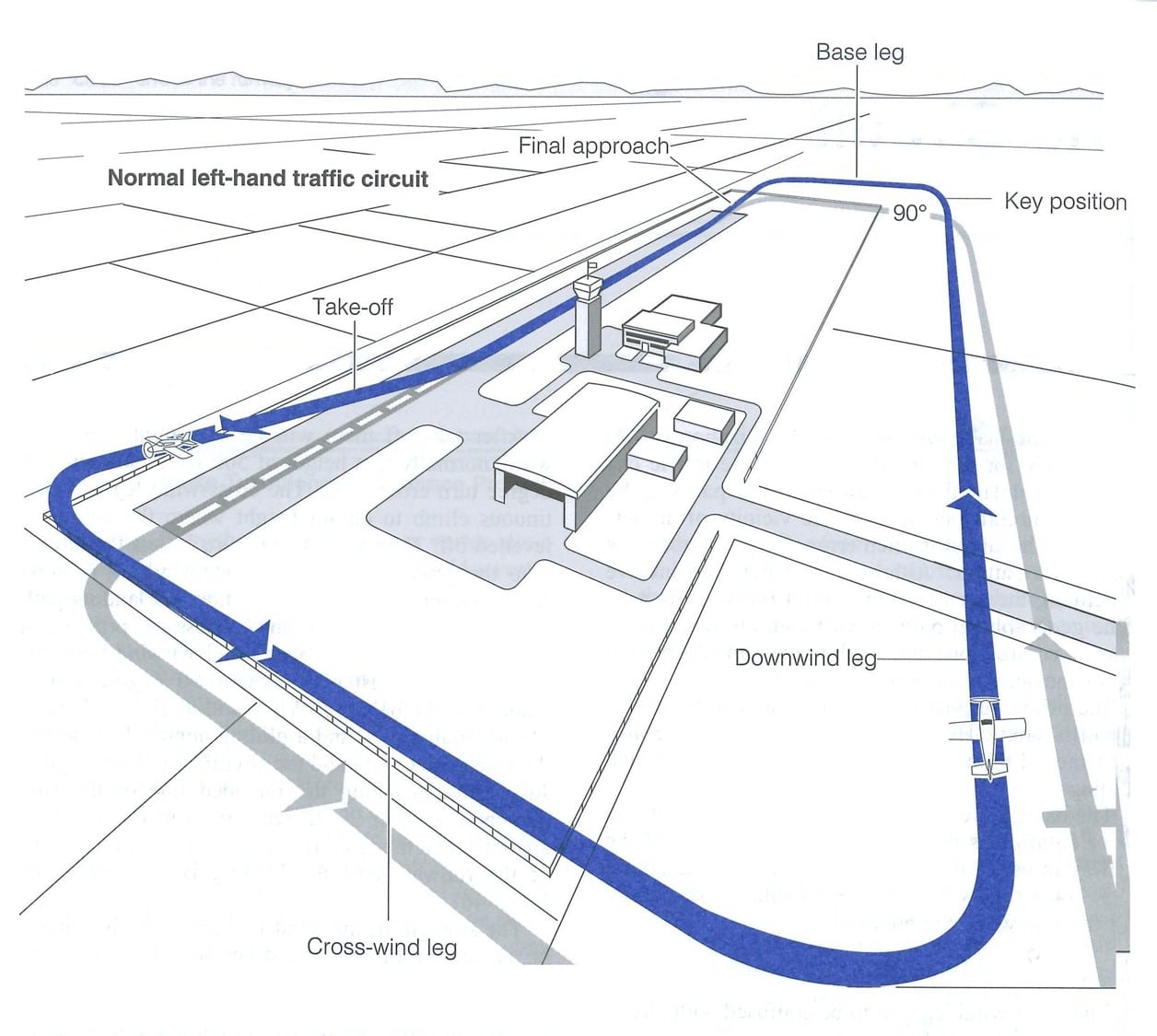

In aviation the two riskiest, most critical aspects of a flight are typically the take-off and landing, mainly because of the combination of relatively low airspeed and proximity to the ground. Should a problem occur, the pilot has little time, height and airspeed with which to manage the emergency.

Early in their training, aircraft pilots practice ‘circuits’ to build up their experience. A circuit is a take-off, a quick loop around the perimeter of the airport, then a rolling landing and take-off again.

Once the trainee pilots become proficient, the instructor will start to introduce complicating factors. These are typically a simulated emergency of some sort.

A radio failure would mean the pilot needs to communicate with the air traffic control tower via other methods before landing safely. A stuck throttle on landing would mean a fast and shallow approach before landing. Or a particularly nasty scenario, an engine failure shortly after take-off, in which the pilot does the best they can with the height and speed available.

Rather than ignoring the risk and hoping it never happens, pilots practice over and over so that if the worst does happen, they can react quickly, evaluate the options available and take the most appropriate course of action without panicking.

Orchestrating complex events

Another analogy is when complex procedures should be rehearsed, much like staging a play. Everyone learns their lines individually, then bits of scenes are practised together. Then gradually the actors get closer to the real performance by adding in the stage directions, props and costumes, with a dress rehearsal before the opening night.

All this practice doesn’t guarantee a perfect opening night, but hopefully it serves to catch all the big screw-ups beforehand.

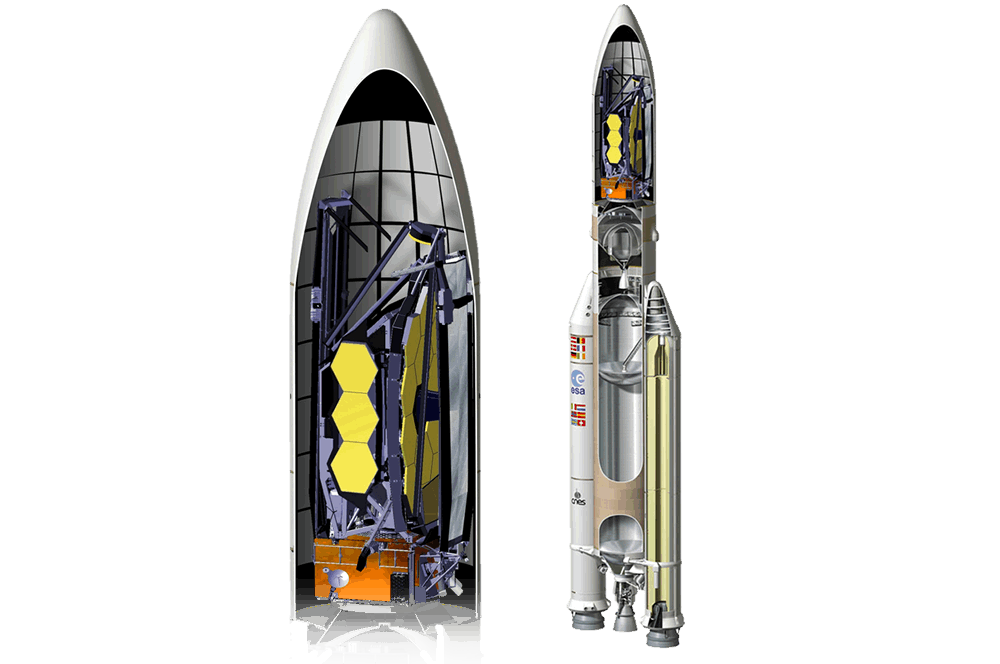

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is a particularly nail-biting example of this. Its design was so large that it had to be carefully folded up to fit inside the rocket before being launched into orbit. Once in orbit a million miles from Earth, 344 separate unfolding operations each had to complete successfully, otherwise the $10 billion telescope, and the 20+ years of planning and development leading to that point, would have been wasted. At that distance, there was no possibility for repairs — no plan B.

Alistair Glasse is the commissioning lead for MIRI (mid-infrared instrument), one of the four major instruments on-board the JWST.

“As commissioning lead, my role has been to ensure that the instrument we’ve built meets the needs and aspirations of astronomers and scientists. We delivered MIRI to NASA in 2012. But our involvement didn’t stop there. Since 2012, MIRI has been getting built into bigger and bigger subsystems within the observatory, so we’ve been carrying out rigorous testing at every stage.

“For example, in 2017 in Houston, we built up the entire observatory, all the instruments and the telescope, in a huge vacuum chamber. It was then cooled down to its operating temperature in space, which is around 40 kelvin (approximately -230°C), before we ran end to end tests. This was to check the instruments could be aligned and cope with the rigours of space.”

“James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) final rehearsals before launch”, Alistair Glasse, Project Scientist, Commissioning Lead at the UK Astronomy Technology Centre, writing on the UK Research and Innovation blog

Seemingly against the odds — although really due to the intense preparation of all the teams involved — the unfolding of JWST in space went perfectly.

“After the last wing deployment, more than one person made comments like, ‘it seemed so simple; did we overstate the complexity and difficulty of the deployments?’”

“The perfection of the deployment execution and the subsequent activities reflects directly on how hard everyone worked and the diligence and sacrifice it took on the part so many people. The fact that it looked simple is a tribute to all those over the years who have worked towards Webb mission success.”

“The Webb Team Looks Back on Successful Deployments”, Bill Ochs, Webb project manager, NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center

Final thoughts

As product managers, we try understand the hidden complexity behind our decisions, and be sensitive to the factors that affect our decisions. It’s a good approach to consider the likelihood and impact of our what-if scenarios and have appropriate backup plans.

When faced with particularly critical risks, it is better to embrace and practice the scenarios until they become mundane, rather than hoping the risky eventuality never materialises.

Leave a Reply