Sorting the signal from the noise — a guide to fact-checking

The word ‘signal’ is a metaphor for the patterns and meaning that are hiding in data. In electronics, signals must be separated from noise to be useful.

“How to Separate Noise from Meaning in Big Data”, George Dealy, Dimensional Insight, 17 November 2017, retrieved 4 March 2022.

What people say they do and what they actually do are often different. What people say they want and what they actually need are also often different — that’s why we can’t simply ask users to design their ideal product and implement it verbatim.

One of the most important, and arguably hardest jobs we have as product managers is to work with our team to sift through information, read between the lines, and verify what is fact and what is merely opinion.

In this article #

- Introduction

- Discovery in user groups

- The trouble with online content

- You can stop here if you want

- Deliberate manipulation of the facts

- Information disorders

- The fact-checkers

- Operation Fortitude South

- Fake-fact check or fake fact-check?

- Checking sources with a critical eye

- Final thoughts

- Further reading

- Fact-checking organisations

Discovery in user groups

Right at the beginning of a new product idea, you’re in the midst of chaos. You’re trying to figure out whether the idea is worthwhile to pursue or not, which is hard enough. But more fundamentally you’re trying to find out whether you’re even talking to the right group of people to begin with.

Even before the global pandemic forced us all into perpetual video calls, enterprising product people would conduct their discovery and user research by joining representative user groups (hopefully in an ethical and transparent manner): local Meetups, LinkedIn professional groups, communities with a common interest, and so on.

Whether as active participants or simply as observers, they could gain an understanding of that group’s context, needs, problems and language. It wouldn’t be their only source of user research, but it would be a starting point.

The trouble with online content

User-generated content, typically as you’ll find in an online forum or on social media, is always a mixture of bias, opinion, truth, half-truth and falsehood. People can say and write things they fundamentally believe to be true, while still being objectively and factually incorrect.

Online groups can easily become echo chambers1 that can disproportionately reinforce a point of view, whether it reflects the truth or not.

And this is fundamentally the problem we have when we research our users. Consensus doesn’t necessarily imply rightness or wrongness, just that people share a particular point of view. As product managers, we have to view the user research we gather with a more critical eye.

You can stop here if you want

You could stop reading here and and reflect on what your user research is really telling you, particularly if you’re primarily researching your target users in online groups, or by analysing what they say, rather than what they actually do. Don’t rely solely on one type of user research, and be vigilant to why people may be saying something as well as what they’re saying.

I was going to write this article about sorting the signal from the noise when dealing with user-generated content anyway. However, the invasion in the last couple of weeks of Ukraine by Russia’s forces, and the subsequent chatter online have only served to reiterate the need for all of us, not just product people, to be able to examine what we watch and read online with a more critical eye.

If you want to dive deeper into the rabbit hole of determining the trustworthiness of information, along with some historical background, and some practical advice on fact-checking, read on.

Deliberate manipulation of the facts

It’s one thing when we come across unintentional bias and ill-informed opinions in online forums and social media. It’s quite another when people with a particular agenda deliberately manipulate information to amplify a point of view they support.

Let’s look at an example. You may remember the disparity between the various claims made about public attendance at Donald Trump’s presidential inauguration ceremony.

“But, you know, we have something that’s amazing because we had — it looked — honestly, it looked like a million and a half people. Whatever it was, it was. But it went all the way back to the Washington Monument. And I turn on — and by mistake I get this network, and it showed an empty field. And it said we drew 250,000 people. Now, that’s not bad, but it’s a lie. We had 250,000 people literally around — you know, in the little bowl that we constructed. That was 250,000 people. The rest of the 20-block area, all the way back to the Washington Monument, was packed. So we caught them, and we caught them in a beauty. And I think they’re going to pay a big price.”

Transcript of remarks by President Trump at CIA Headquarters (on 21 January 2017), FactCheck.org, retrieved 6 February 2017 via the Internet Archive

An article by Reuters showed the disparity in attendance numbers at comparable times with photos taken from the same position at the inaugurations of Barack Obama in 2009 (right-hand photo) and Donald Trump in 2017 (left-hand photo).

In an unusual and fiery statement on Saturday night, White House spokesman Sean Spicer lashed out about tweeted photographs that showed large, empty spaces on the National Mall during the ceremony on Friday.

“This was the largest audience ever to witness an inauguration, period. Both in person and around the globe,” Spicer said in a brief statement. “These attempts to lessen the enthusiasm about the inauguration are shameful and wrong.”

Washington’s city government estimated 1.8 million people attended President Barack Obama’s 2009 inauguration, making it the largest gathering ever on the Mall.

Aerial photographs showed that the crowds for Trump’s inauguration were smaller than in 2009.

“White House accuses media of playing down inauguration crowds“, Jeff Mason, Roberta Rampton, Reuters, 22 January 2017, retrieved 12 March 2022

The effect of this onslaught of ‘alternative facts’ before, during and after Trump’s presidency, even in the face of seemingly obvious evidence to the contrary, was to undermine the public’s trust in the media. If you can’t be sure about who and what to believe, then you start to dismiss truth and fiction equally. And that worked in the Trump administration’s favour.

And in the absence of verifiable, trusted sources of facts, people will fill the information void with their own theories and opinions, which can then be amplified by near-universal access to social media, no matter how irrational they may seem.

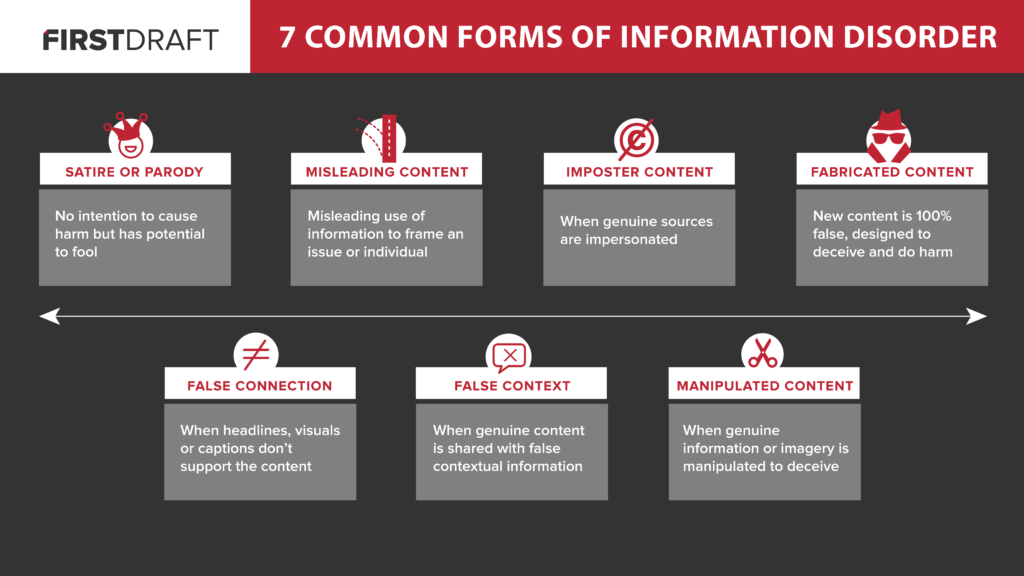

Information disorders

Claire Wardle refers to these and other types of unintentional and deliberate disinformation in the Verification Handbook For Disinformation And Media Manipulation as ‘information disorders’:

There are three main motivations for creating false and misleading content.

The first is political, whether foreign or domestic politics. It might be a case of a foreign government’s attempting to interfere with the election of another country. It might be domestic, where one campaign engages in “dirty” tactics to smear their opponent.

The second is financial. It is possible to make money from advertising on your site. If you have a sensational, false article with a hyperbolic headline, as long as you can get people to click on your URL, you can make money. People on both sides of the political spectrum have talked about how they created fabricated “news” sites to drive clicks and therefore revenue.

Finally, there are social and psychological factors. Some people are motivated simply by the desire to cause trouble and to see what they can get away with; to see if they can fool journalists, to create an event on Facebook that drives people out on the streets to protest, to bully and harass women. Others end up sharing misinformation, for no other reason than their desire to present a particular identity. For example, someone who says, “I don’t care if this isn’t true, I just want to underline to my friends on Facebook, how much I hate [insert candidate name].”

“The Age of Information Disorder” by Claire Wardle, Verification Handbook For Disinformation And Media Manipulation, edited by Craig Silverman, retrieved 12 March 2022

The fact-checkers

There are many fact-checking organisations. Some are independent, such as Snopes (checking stuff online since 1994), ProPublica, and Full Fact. Others are attached to organisations such as Poynter’s International Fact-Checking Network, The Annenberg Public Policy Center’s FactCheck.org, and BBC’s Reality Check.

Not unreasonably, some people will question the impartiality of the fact-checking organisation itself. But even if your starting premise is that everything online is untrustworthy until proven otherwise, a good fact-checking service will be run and funded transparently, and will show its working and sources when checking purported facts.

You don’t have to rely on just one fact-checking organisation; major claims will probably be checked by multiple organisations independently. Triangulate your research.

Operation Fortitude South

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has triggered both physical and online conflicts. The use of propaganda and disinformation in war, either to confuse the enemy or sow the seeds of dissent amongst an enemy’s citizenship, is not a new development.

In World War II, Allied forces used their intelligence advantage to mislead the German high command into believing that the D-Day invasion of north-western Europe would begin at the most obvious sea crossing at Pas-de-Calais. In fact, the Allies were planning to land further south at Normandy. This gambit — Operation Fortitude South — worked, and the majority of German units was posted to Pas-de-Calais, leaving Normandy comparatively undefended.

The deception was multi-faceted. Double agents ‘leaked’ fake information about Allied plans and movements to the German forces. Operation Quicksilver faked physical troop movements by mocking up realistic-looking landing craft, and positioning dummy tanks and military vehicles around south-east England. This became known as the “Ghost Army”.

And thanks to the code-breakers at Bletchley Park, the Allies had cracked not only the more well-known Enigma enciphering system used for air, land and sea traffic, but also the obscure and far more complex Lorenz system used by German high command. The Allies could therefore listen in on German communications at all levels without detection, allowing them to gather intelligence and to check whether their misdirection had worked.

With Operation Fortitude South the Allied forces successfully weaponised disinformation against Hitler’s forces.

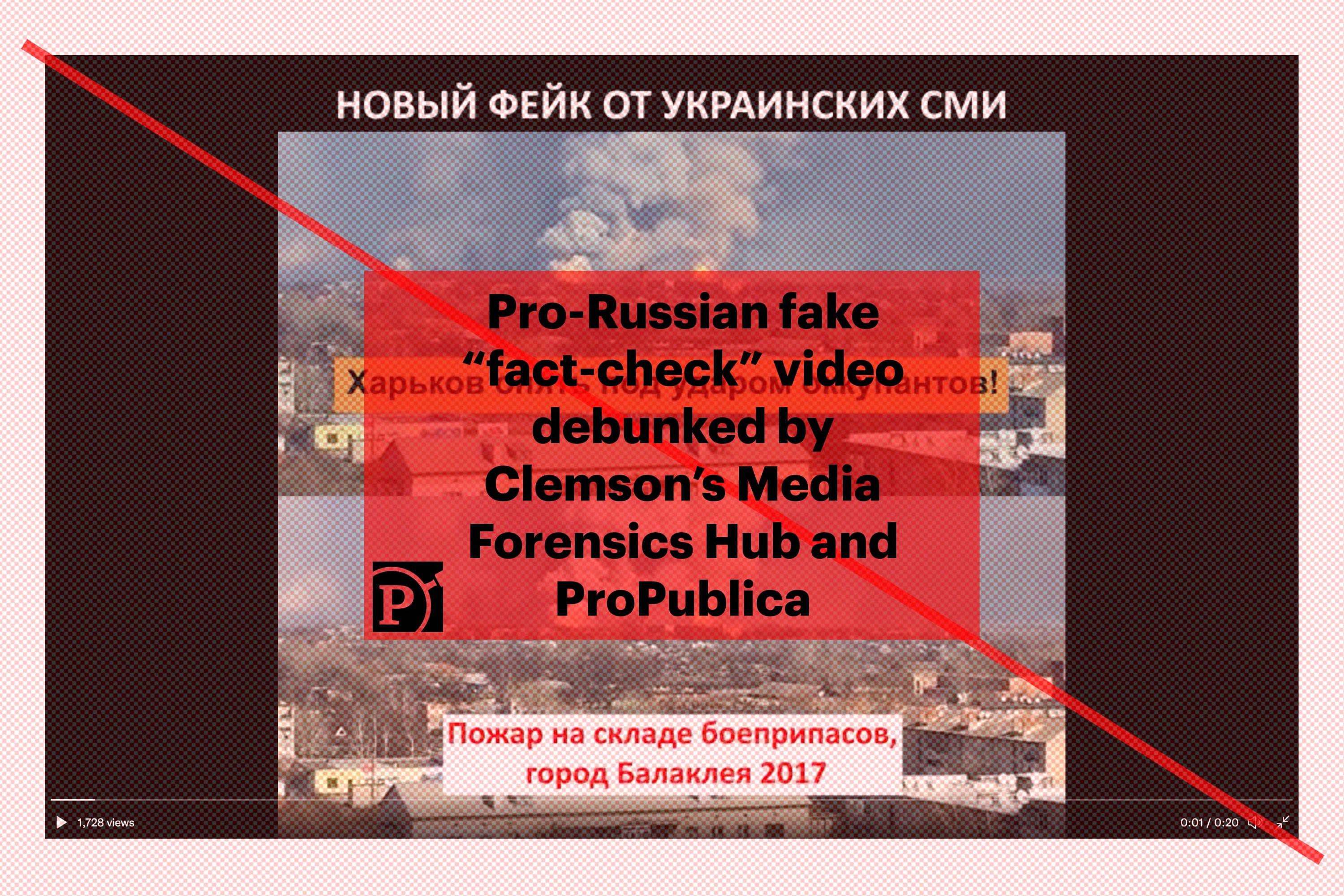

Fake-fact check or fake fact-check?

It’s not a massive surprise that both sides in a conflict will want to control the narrative. With the invasion of Ukraine, Putin is seeking both to discredit Ukrainian accounts of the conflict so as to delay or mitigate Western support, and to justify the invasion internally to the Russian public, which is not uniformly in favour of the military action.

And this is where it gets a bit complicated and meta.

Fact-checkers already have to contend with the barrage of propaganda and fake news being issued by state-controlled Russian media. A new development is the use of fake “fact-checks”.

Craig Silverman and Jeff Kao report for ProPublica that pro-Russian social media posts pose as a legitimate fact-check of Ukrainian propaganda. The intended message: don’t trust footage published by Ukraine of Russian missile strikes. The problem is that there’s no evidence that the video being debunked was ever circulated in the first place. In other words, the “fact-check” itself is disinformation.

If believed, it causes people to doubt legitimate Ukrainian reporting of Russian attacks. Even if not believed, it casts doubt on legitimate fact-checking services. It’s a particularly insidious form of disinformation designed to undermine the public’s trust in the media and further confuse fact with fiction.

Checking sources with a critical eye

So how can we even begin to figure out whether what we read and watch online is factually accurate?

While the original Verification Handbook (book one of what has become three books covering different aspects of the topic as it’s evolved over the years) is more geared towards journalists verifying citizen reports of disasters and significant events, its principles of checking sources are worth noting here:

Verification Fundamentals

Put a plan and procedures in place for verification before disasters and breaking news occur.

Verification is a process. The path to verification can vary with each fact.

Verify the source and the content they provide.

Never parrot or trust sources whether they are witnesses, victims or authorities. Firsthand accounts can be inaccurate or manipulative, fueled by emotion or shaped by faulty memory or limited perspective.

Challenge the sources by asking “How do you know that?” and “How else do you know that?”

Triangulate what they provide with other credible sources including documentations such as photos and audio/video recordings.

Ask yourself, “Do I know enough to verify?” Are you knowledgeable enough about the topics that require understanding of cultural, ethnical, religious complexities?

Collaborate with team members and experts; don’t go it alone.

Verifying user-generated content

Start from the assumption that the content is inaccurate or been scraped, sliced, diced, duplicated and/or reposted with different context.

Follow these steps when verifying UGC:

— Identify and verify the original source and the content (including location, date and ap-

proximate time).— Triangulate and challenge the source.

— Obtain permission from the author/originator to use the content (photos, videos, audio).

Always gather information about the uploaders, and verify as much as possible before contacting and asking them directly whether they are indeed victims, witnesses or the creator of the content.

“Creating a Verification Process and Checklist(s)” by Craig Silverman and Rina Tsubaki, Verification Handbook, edited by Craig Silverman, retrieved 12 March 2022

Final thoughts

It’s not new that people, organisations and governments are seeking to influence and persuade us to believe and do things. What else is advertising other than a means of persuasion?

The means of influencing us are also becoming increasingly sophisticated and less obvious. We have industrialised the tools that can be used equally for legitimate reasons and for deception. You can generate a plausible real-time deepfake video on a high-end desktop, or create a reasonable facsimile of your voice pattern for $24. It’s almost impossible for an average member of the public to detect manipulation of photos or video footage without knowing what tell-tale artefacts editing leaves behind.

The considerations we have to make are whether the intent behind that form of influence is positive and genuine, or whether it is damaging and misleading — both for us and the users of our products. More than ever, we have an ethical responsibility to apply a critical eye to the user research we gather, and to sort the signal from the noise.

Further reading

“First Rule of Usability? Don’t Listen to Users” by Jakob Nielsen, 4 August 2001, Nielsen Norman Group, retrieved 12 March 2022

“When to Use Which User-Experience Research Methods” by Christian Rohrer, 12 October 2014, Nielsen Norman Group, retrieved 12 March 2022

Transcript of remarks by President Trump at CIA Headquarters (on 21 January 2017), FactCheck.org, retrieved 6 February 2017 via the Internet Archive

“White House accuses media of playing down inauguration crowds“ by Jeff Mason and Roberta Rampton, Reuters, 22 January 2017, retrieved 7 February 2018

“Conway: Press Secretary Gave ‘Alternative Facts‘”, NBC Meet The Press, 22 January 2017

“QAnon: What is it and where did it come from?” by Mike Wendling, BBC News, 6 January 2021, retrieved 12 March 2022

“The Age of Information Disorder” by Claire Wardle, Verification Handbook For Disinformation And Media Manipulation, edited by Craig Silverman, retrieved 12 March 2022

“D-Day Deception: Operation Fortitude South“, English Heritage, retrieved 12 March 2022

“Ghost Army: The Inflatable Tanks That Fooled Hitler” by Megan Garber, The Atlantic, 22 May 2013, retrieved 12 March 2022

“How Lorenz was different from Enigma” by Captain Jerry Roberts, The History Press, retrieved 12 March 2022

“The Spectacular Collapse of Putin’s Disinformation Machinery” by Tom Southern, WIRED, 10 March 2022, retrieved 12 March 2022

“In the Ukraine Conflict, Fake Fact-Checks Are Being Used to Spread Disinformation” by Craig Silverman and Jeff Kao, ProPublica, 8 March 2022, retrieved 12 March 2022

“Creating a Verification Process and Checklist(s)” by Craig Silverman and Rina Tsubaki, Verification Handbook, edited by Craig Silverman, retrieved 12 March 2022

“Sassy Justice” by Trey Parker, Matt Stone and Peter Serafinowicz

Fact-checking organisations

International Fact-Checking Network (Poynter)

FactCheck.org (The Annenberg Public Policy Center)

Reality Check (BBC)

Notes #

- An echo chamber is “an environment in which a person encounters only beliefs or opinions that coincide with their own, so that their existing views are reinforced and alternative ideas are not considered”, definition provided via Google from Oxford Languages, https://languages.oup.com/google-dictionary-en/ ↩

Leave a Reply