5 product leadership lessons learnt from the UK’s Ministry of Justice Digital team

Between 2014 and 2015, I was head of product for the UK’s Ministry of Justice Digital team. Just after I gave a talk on a converted cinema stage with an absolutely massive screen in Zurich, Switzerland.

I talked about the 5 product leadership lessons I’d learnt about digital transformation and working with autonomous, empowered delivery teams. It’s called Digital Justice and you can watch it below after the break. There are also slides and a full transcript under the video.

Video

Slides

Transcript

How I found myself in product management

Good, so you can hear me? Excellent! So, yes, thank you very much for coming along to my talk today. I’m going to be talking about my time in the Ministry of Justice. But as any good talk needs to start, there’s the obligatory stuff about me. At university my path to product management was quite a strange one. I studied Classics, so Latin and Ancient Greek, which is not the most obvious way to get into product management, or indeed technology.

But when I was at university, I was actually learning to fly with the RAF [Royal Air Force] because had dreams of learning to fly these things. But in actual fact, what I was really flying was this: which was slightly different! But I wasn’t very good at it. So, I had to get a job. Okay. That meant I was working for about twelve years in a variety of different software companies. Starting out with a startup called Zeus Technology. But then working in much larger organisations like Experian and Iron Mountain.

And over the course of those twelve years I learned a few things. And I kind of felt that I was only doing product management in one way; I was learning only how to do it in one particular way. So I thought wouldn’t it be good if I could learn how to do product management in lots of different ways, with lots of different companies, of lots of different sizes, in many different markets. So I started up Product People, which was the company we mentioned earlier.

And this gave me the opportunity to work with all these different types of companies. So in the last three years, I’ve had the opportunity to learn a great deal more. I’ve worked with companies like the NIKE Foundation to build a charitable mapping application for people in Rwanda; I’ve worked with the BBC, done training with them. And I’ve worked with other organisations such as the Ministry of Justice. And that’s what I’m going to be talking to you about today.

The Ministry of Justice

So the Ministry of Justice. This is essentially a UK government organisation that deals with the things you’d expect. So prisons, courts, but it also has this strange thing called Ministry of Justice Digital – MOJ Digital. And this was essentially a startup that they were building within the Ministry of Justice. So, what this meant was, as an organisation, we decided that there was a better way of doing things. And probably the best way of doing that is to play a short video so that it will explain in their own words what we did.

Transforming the justice system

[MUSIC PLAYS]

Our mission here is to build end-to-end digital services that meet the needs of users and save the public money. We put the user at the heart of everything we do here, and that drives a lot of innovation in the way that we think about how our services should be designed and delivered.

Users can – citizens can self-diagnose whether they may be eligible for CLA [Civil Legal Aid]. We take what we call an agile approach to product development here, so users are actually involved in the design and the testing and the development of the products.

Much of the work that we do is about challenging existing ways of doing things.

It’s very easy to assume that you know something, and often we do have a good idea of something, but we don’t actually know until we know. And knowing means testing, knowing means bringing stakeholders onto your side, knowing means being able to express what you need to have done and why you’re doing it.

Collaboration is at the heart of what we do at Digital and we’ll always be looking for ways to work with more people across the organisation.

[MUSIC PLAYS]

A startup within the Ministry of Justice

Okay, so the Ministry of Justice Digital – we were a startup within the Ministry of Justice. And what that meant was that we were going to deliberately take a different way to building things.

Our aim – our mission, if you like – was to build digital services so good, that people would prefer to use them. And this was fundamental – a fundamentally different way of working in government. We were an organisation of 150 people, agile, digital, customer-centric minded people, working to put the needs of the users first. And for us, our users were the 65 million citizens in the UK.

All of these people at some point in their lives would have some reason to interact with the justice system. They might, for instance, need to make a small claim to get some money back from someone, and would have to go to court to do that. Or perhaps, you know, they might have a speeding fine and might need to pay that. Or perhaps they may have friends or relatives, who for whatever reason end up in prison. And they might get involved in that particular way.

What we had here was an organisation of about 70,000 people, the Ministry of Justice, and we were a very small part within that. We were 150 people of these digitally-minded people. And so what we were trying to do was to say, every single time a person interacts with the justice system, we want to make that experience as good as it possibly can be. Because the reason being was that these people were only ever having to interact with the justice system when something bad has happened!

You don’t want to get a parking fine, you don’t want to get caught by a traffic camera, you don’t want to have to go to court if you don’t need to. All these moments where people need to interact with the justice system were stressful and painful and generally not very much fun.

And so our objective was not so much to try and make these experiences fun or pleasurable in that respect, but at least to make them as frictionless as possible. To make them as simple and straightforward as possible, to not make the existing situation any worse, to not make people feel any worse than they already did when they were in that situation. So the reason why I’m here to talk to you today is not to convert you and say that this a fantastic way of working, but to give you some practical lessons that you can apply in your own organisations.

So really I’m here to tell you how you can take what I’ve learnt over my 8 or so months at the Ministry of Justice as head of product, and turn that into things that your organisation can actually start doing tomorrow.

5 ways to change your organisation

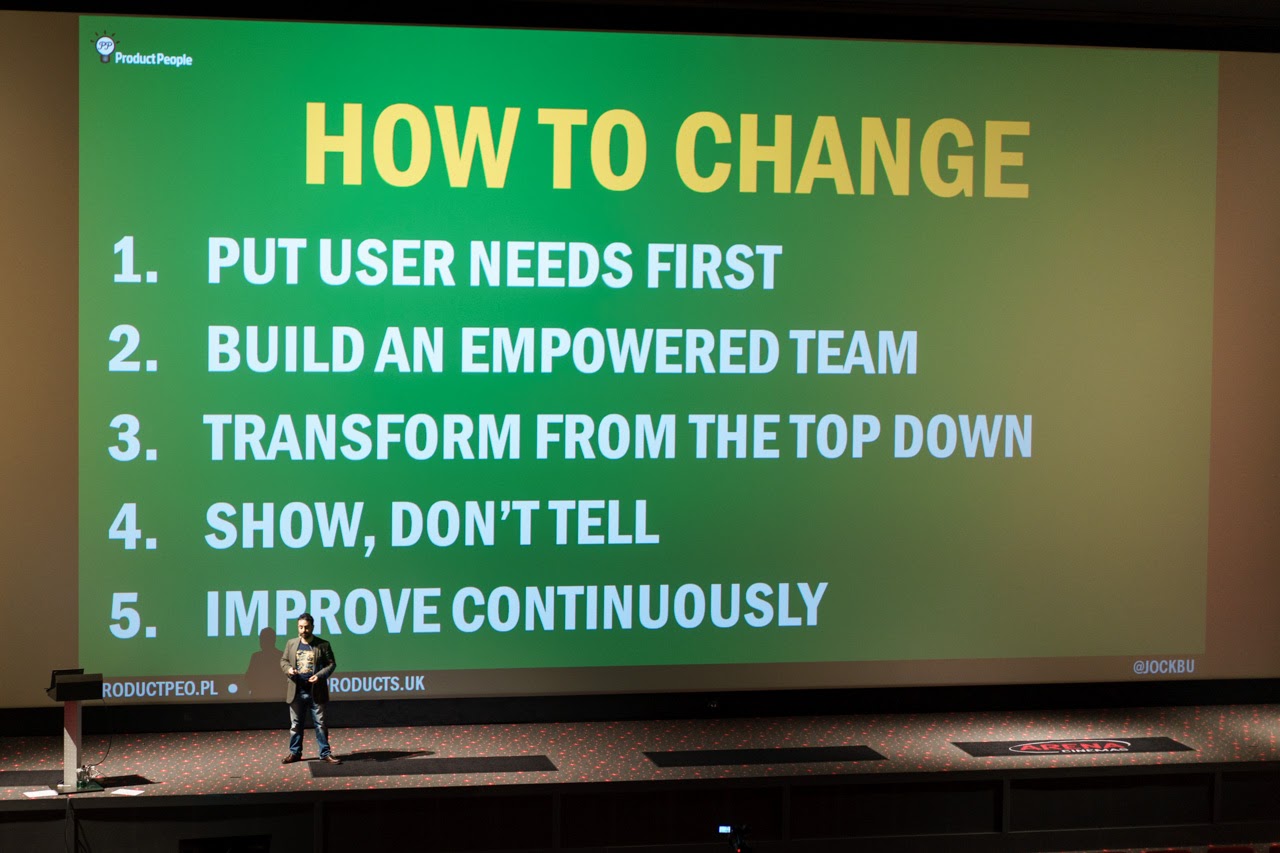

So, we’ve got 5 ways to start with, but there are many other ways, I’ll just focus on these ones for the purposes of this talk.

The first and foremost piece is to put the needs of your users first, and I’ll expand upon these points in a minute, so we can talk in a bit more detail.

The second one is about building an empowered team. Coleman mentioned how it’s important to build an empowered team, as did Martin and Tim earlier on in the keynote.

We need to think about transforming the organisation from the top down. We’re looking beyond just the pure product management piece, we’re actually saying how can we change our organisation to give us the environment we need to do product management the right way.

We’re going to build a culture of showing and telling – show, don’t tell. This idea that demonstrating what we’ve done is more important than talking about what we’re going to do.

And also, again something that we’ll probably touch upon repeatedly throughout the day if we’re talking about agile, lean, continuous improvement and continuous deployment. We’re going to be talking about this kind of thing as well. How we actually improve continuously, and what we did to make sure we did that.

#1 Put user needs first

So first of all: putting user needs first. The old way – we saw something similar to this a moment ago. How many people recognise this in their own organisations? Where you would be capturing requirements up front, building a big laundry list of things that you wanted to build into the product. And then we spend time and money, and if you’re a government organisation, that means going out to tender, to ask various large organisations like the Accentures, the Logicas and the Capitas of this world to be able to bid to build that product from that list of requirements.

And then the build happens, and maybe it takes 6 months, maybe it takes 12 months. If it’s government, it’ll probably take a lot longer. (thank you) And then at the very end of this process, so when this big IT project has gone through the process and has come out the end 18 months late, 200 million over budget, we then actually put it in front of the users. And funnily enough, they’re not very happy about it.

Because the product’s been designed by people who have no understanding of the needs of the users, and as a result, the resulting product doesn’t meet the needs of the users. So of course they’re unhappy.

A better way of working

There’s a better, and a different way of doing this. So the way we talk about it is about this process of starting with user needs. We talk about discovery, where we go out there, and before we go anywhere near trying to build anything, we go out and understand what we know about the people who we’re trying to help with this particular product or service. We understand what their needs are, what their problems are, where they feel stressed, what they find difficult to understand. And we discover all of these things that, on day 1, we don’t know yet.

And so what that does, is it allows us to say – okay we now know a few things, but we still don’t know everything. So let’s maybe try out a few ideas. And then we move into the Alpha stage. And that’s where we start experimenting. That’s where we start drawing up some sketches. We start maybe doing some working prototypes.

But all the time, we’re putting them back in front of users to make sure that we’re on the right track. Because we don’t know anything, we’re not the users. So we need to make sure we’re always continually checking back with the people that we’re building this service for. Because what that allows us to do is to make sure that we’re not going to make a big mistake. And if we do find ourselves moving off track, we can course correct, we can move ourselves back onto track.

Then by the end of Alpha, we really know two things: we know what the problem is reasonably well, and we’ve got a pretty good idea of what’s going to work to solve that problem. Then what we do is we almost throw away all the prototypes, all the mockups we’ve done up until this point. And then we start building it properly. We’re going to build it scalably, we’re going to build it to work for 64, 65 million people in the UK. We’re going to build it to make sure it’s secure, but we’re going to build it using the right technologies in the right way because only now do we really understand enough to be able to do that properly. And then, when we send it live, we’re putting in front of everyone. We’re making sure that we’re still gathering that feedback. And we’re now into that process of continual improvement.

So these 4 phases, we try to move through in about 6 to 9 months. So we take an idea about maybe perhaps improving some aspect of the courts process all the way through to something people are actually using in real life in 6 to 9 months. Now how many of you could say in your organisations that you can do that right now?

So, the point being is, if government can do this in the UK, any of your organisations can. It is possible, but it does require a different way of working.

Booking a prison visit

So let’s take an example: booking a prison visit.

Previously if you were in prison unfortunately and you wanted someone to come and visit you, you’d have to fill out a form like this. This is actually the visiting order for a chap called Ronnie Biggs, who was a very famous train robber in the UK, who stole about several million pounds back in the sixties.

And as a result, what would happen with this form is that it would be sent to the people you want to come and visit you. They’d have to phone up several times to try and book a visit time that was hopefully convenient for them and for the prison. And this whole process would take several rounds, and involve lots of people, and be very bureaucratic, and take a whole bunch of time and effort for everyone involved.

But really, as a visitor, all they want to do is to book a visit. They don’t want to have to phone up several times or fill in forms or make sure they have the right piece of paper with them that’s been stamped by the right people. So actually by focusing in on the underlying user need, as a visitor I want to book a visit, as a prisoner, I want my friends and family to be able to visit me, or as a prison staff member, I wish not to have to deal with logbooks and papers and so on to coordinate these visits. That should all be handled for me.

#2 Build an empowered team

So the second point: building an empowered team. What does this mean? First of all it means hiring brilliant people. So to begin with in the Ministry of Justice, we started out wanting to make some rapid changes. We wanted to make sure that we were actually able to hit the ground running.

So what this meant was that we hired people who were able to start without any training. So we hired experienced, very senior, experienced people to come in on a short-term basis to get the ball rolling, to get things moving.

And essentially this gave us the ability to avoid those problems that sometimes happen when you’re introducing agile or a different way of working into an organisation that’s primarily waterfall or project management or big IT. And the problem was that were trying to avoid, was that we didn’t want people to think that agile or the way of working was failing because we didn’t have people who were really good at it.

So what we made sure was we brought the best people we could in to begin with, then they could really show how the process could work very well, which meant there was no problem or no criticism of the process not being the thing that wasn’t working. So we made sure we hired the best people from the very outset.

Assemble the right team

The second thing we did was to make sure we assembled the right team of people. And so what that meant was making sure we had the right skills to do the right job. So in our case, that meant have dedicated experienced product managers, absolutely. Designers, researchers, content designers, so specifically people with a background in journalism that would allow them make sure that the copy, the writing in the products and services we were building was as easy to understand as possible.

We made sure we had data scientists. We made sure we had specialists in other areas: web ops, continuous integration, all of these different things that we needed to make sure we had the right skills to build the products and services we needed to.

Autonomy, mastery and purpose

Something that Coleman was talking about earlier on: autonomy, mastery and purpose. Autonomy is something that individuals need to be allowed to do the job they’re doing. We set them the goal, we set them the mission, we allow them to do it in the best way possible. Again, in organisations such as the UK government, and the Ministry of Justice, they were very much in that command and control way of thinking. They would issue detailed orders and make sure that people would do things in a very prescriptive, specific way.

Here it was very much about saying, these people know what they’re doing. Let them get on with it. So we gave them the autonomy to do things their own way. We let them work in their own way. So if they wanted to be doing Scrum – great, you can do Scrum. If you want to do Kanban, you can do Kanban, fantastic. If you want to do a mixture of the two, fantastic – do what ever you need to do. Do whatever your team needs to do to get the job done.

We talked about mastery in terms of hiring brilliant people, and that sense of purpose. Many of the people need motivation, and that’s different to the paycheck, yeah? When you’re working for an organisation like the Ministry of Justice, people are there because they want to help people to engage and get access to justice.

So that sense of purpose, what is it your organisation is here to do, why do people get out of bed in the morning to come and work with you, is the kind of thing we’re trying to instil in the people we brought to work with us.

And empowerment means trust. Again, Coleman was talking about this earlier on, but the idea of the generals trusting the squads to do the right thing, to take the objective. In the same way – and this was a really difficult culture change for the Ministry of Justice, and it’s not something we’ve achieved 100 percent yet by any means, it’s something that’s still ongoing – that trust to say, we accept that you know what you’re doing, we trust you to meet the objective, go away and do it and we won’t interfere. That’s one of the hardest things for an organisation to do.It’s giving up control from the top of the organisation to the bottom of the organisation.

So, there are no shortcuts to this one. This is something that will take many years, even in the Ministry of Justice, to do. But it’s something we’re working on, it’s something we need to happen.

Culture is really, really important

Okay – culture is really, really important. For us, every time we needed to celebrate something, we’d celebrate with cake. And it was the way we worked. We also probably went through more Post-It notes than any other organisation that you’d see in the area, but that was the way we needed to work. We needed to work very visually.

So culture, making sure that people want to work and have a desire to work with you is really important. And it’s very easy to break that when you start to take away things like autonomy and a sense of purpose from people.

#3 Transform from the top down …

You need to transform from the top down, you need to instil this desire to empower the people lower down the organisation. And there’s a chap called Tom Loosemore who says, the reason why – one of the ways you can earn trust from organisations is to show what you’ve done, to demonstrate the kind of thing they can get.

So at Mind the Product he spoke a couple of years ago, he said that government ministers should look at the Alpha, the rough prototype and be impressed enough to say, “I want one of those.” And then that’s the way of earning the trust to do a bigger experiment, to do a bigger thing.

It’s also important to build up a track record. So you’ve got two ways of approaching how you deliver things. You could bet it all on one really big product launch and hope that it all goes well, or you could do lots of really small product launches or releases that will allow you to demonstrate a track record of success with much lower risk launches.

If you go for that latter option, the low-risk approach, you can build up that track record of success. And it means that it’s much easier for people to do the next thing thereafter.

And so what we’d do is we’d show things to people. So this lady here in red is Ursula Brennan. She is the permanent secretary for the Ministry of Justice. So she’s essentially the boss. She is the most senior civil servant within the Ministry of Justice, and her job is essentially to make sure that everything within the Ministry of Justice is coordinated and working well.

So we made sure that, even the prototypes, the things that were rough and ready, the things that weren’t quite finished yet, we were showing to her when we got the opportunity, so we could build up that trust of delivery.

… and from the bottom up

But it’s also important to change from the bottom up. We made sure we had an outreach programme, where we would train and encourage people to think in a different way, in a more customer-centric way, a more user-centric way. And that meant our 150 people going out to the other 70,000 people in the Ministry of Justice and teaching them about why it was so important to put the citizens first, to put the users first in this.

#4 Show, don’t tell

The fourth aspect of this is show, don’t tell. And it’s kind of intertwined with all of the things we’ve been talking about.

One of the reasons why it’s important to show, rather than tell, is because we learn from our peers. What happens is, when people see something happening that’s of benefit to them, they’ll copy it. There’s a gentleman called Alex Pentland, who’s a professor at MIT, and he says that if you see lots of people experimenting with an idea, people with whom you have strong social ties, there’s a high likelihood you’ll adopt that behaviour. And because he’s a data scientist, he has the stats to prove this. So he did experiments on Facebook with 60 million people to demonstrate how you could influence whether people chose to vote in a national election or not.

And so he shows that if you, your peers, the people within your organisation, if you are seen to be doing something that’s of benefit to you, your peers will copy your behaviour because it’s going to be of benefit to them as well.

Show the thing

There’s also a lady called Leisa Reichelt. She was the head of user research at the Government Digital Service in the UK, now she’s gone over to do the same job in Australia at the Digital Transformation Office. And she very much encourage this idea of show, don’t tell. Because they really valued showing what they’ve done, not talking about what they’re going to do.

So here’s us, this is my team, at the Ministry of Justice, showing what they’ve learnt. So we’ve just done a discovery exercise. We’ve learnt some things from the kind of people that we’re going to be working with, in this case this is looking at the criminal justice system. And so what we’re doing here is we’re showing what we’ve learned.

We take 30 minutes a week, every Thursday at 3pm. We have a few slots, five minutes to show something we’ve learned that will be of value to the people we work with. And then we take some questions.

We have 3 or 4 of those 5-minute slots each week, and everyone can come along. And it’s not just from our team, it’s an open invitation. Anyone in the Ministry of Justice could turn up to these show and tells. So that’s what we made sure we did to show what we were learning, to show what we were building. And it could be a technical thing, it could something we learned from market, it could be whatever. But the point being was that it was always an opportunity to show and be transparent.

And so here’s one of the things we actually pulled out. These are the results of discovery, and this is a user journey map, from potentially preventing a crime to then, what happens to people after a crime has occurred.

Sit together

There’s also the piece about sitting together. So we talked about colocation. Again there’s lots of great research that talks about the power of generating ideas by making people sit together and actually talk to each other. As they were saying, take the earphones out – you know? Actually talk to each other. But it worked not just for the teams that we were building the products with, but also with our stakeholders.

So it was really, really important for that collaboration. If you were sitting together on the same side of the desk, you’re talking about the same thing, you’re understanding the same context, you’re understanding the same problems, and you’re ultimately moving towards the same goals, then obviously you’ll be much more likely to achieve a good product at the end.

So here’s the kind of things we’d do. This is Kelly, one of our researchers, going off to the courts to see how people fill in a particular form. And we don’t necessarily want to build a better paper form, but by understanding the problems people were having the existing forms, we could then make a better digital service.

And then, all of our outputs, we’d write up, and hence we use all the Post-Its in London. We’d put them on the wall. Everything we learned, we’d put up there. So here on the left we’ve got one of the columns with all of our user personas, and these are real people, and over on the right here we’ve got some user stories that we’re building up as we learn new things.

#5 Improve continuously

Okay – last point: improving continuously. We talked about the prison service earlier on, so I wanted to show what we actually built from that. What we’ve got here are three snapshots as we went through the process. Here’s one of Alpha, very early on. Quite early mockup, doesn’t really do anything but it looks nice. We’ve got the Beta where we’re really starting to solidify, maybe experiment with a couple of ideas. And then, over on the right here, we’ve got the final version and thing that went live.

But all of these three versions were put in front of people to check that we were on the right track. And we learnt different things. We learnt that the text needed to be made more easy to understand, needed to be shorter and more bulleted to make it easier to understand.

We tried this kind of workflow piece to see if that would help people understand where they were in the process. But then we actually removed it again in the live version because found it wasn’t helping.

We played around with different ways of capturing the date of birth, and we found that actually in the final version, having a free text field for our particular users happened to be a better way of doing it. And even the name, we A/B tested. We looked at ways of making sure that the name of the service reflected what people were actually searching for.

So we changed it from “Prison Visits Booking” to “Visit Someone in Prison”, because that’s what people were actually trying to do.

So as we were going along, we were continually learning, continually iterating.

Continuously improve our processes also

The last piece of what we did was, how do we improve not just our products, but our processes? So we had regular retrospectives both within the individual agile teams, but also within the broader team organisation. So we’d have these regular retrospectives with the whole 160, 150 people of us, would get together and figure out how can we as a department work better.

Recap

So to summarise: put user needs first. They are, after all, the people who are going to be using your products, so you need to understand what their problems are, and how best you can solve them.

2: You need to build an empowered team. And that comes from recruiting brilliant people, of the right skill sets, and giving them the autonomy to do the right thing.

You need to transform from the top down, you need to change the way the organisation thinks and works by earning that trust to allow the teams to have that autonomy they need to do their job right.

The fourth thing is show, don’t tell. Show the thing you’ve delivered. Don’t talk about the thing you’re going to build.

And the fifth one is improve continuously, both your product and your processes internally.

So – all of you – here’s your mission. Go out there, build digital services and digital products that are so good, people will prefer to use them.

Thank you very much!

[APPLAUSE]

Questions from the audience

[MC] Perfect! I’m sure there are many questions. I want to give one or two – time for one or two questions. Please, go ahead, raise your hand.

[AUDIENCE MEMBER] You were talking about show, don’t tell.

[JOCK] Yes!

[AM] But I’m sure you had a lot of problems with people within a company that were asking for your future plans. How did you react to that?

[J] Yes, that’s a very good question. So one of the things we had was a very open, transparent roadmap. In one of our seating areas we had these big screens, and so we had about a 6 foot, 8 foot high wall on which we had our roadmap.

And so we tried to be as open and transparent about what was happening and what was going on. We also had stand-ups each week to make sure the roadmap itself was updated. But when people were asking what was coming up, what’s coming up, when is this going to be delivered, when is this going to be delivered, if it was within a particular product, we could say, “come along to the stand-ups with the team, and they’ll show you what’s coming up, because you’ll see what’s on the backlog, you’ll see what the team’s working on today and for the rest of the week, and you can ask questions if you need to.”

If you’re talking more in terms of what the department is doing, then we’d look at the roadmap. And the roadmap would have three areas: what we’re doing right now – we’re pretty sure about, because we’re doing it right now – what we’re going to be doing next, again we’re pretty sure what the next thing was going to be – and everything else, what’s coming later. And that could be a whole bunch of stuff that may or may not happen in different orders.

[MC] Super! We’re out of time. I’m sure there’s lots of opportunities to catch up with Jock. Jock – thank you very much.

Leave a Reply