68: 4 common user persona mistakes

I’m writing about 100 things I’ve learned the hard way about product management. You can catch up on the previous entries if you like.

User personas can be a valuable visual reminder for your teams about the people relying on your product. More often than not, user personas instead end up being just a laborious way to decorate the walls. Are you making these common mistakes?

In this article #

1. Writing them too early

One of the first things many people do when embarking on a new product is to write their user personas. They then declare them complete, don’t update them again for years, then wonder why they never bore any relation to their actual users.

At the beginning of a new product, you may feel you already have a pretty good idea about what your users look like, particularly if you have an existing product out there. Unless you’re already in the good habit of meeting with users a minimum of two hours every six weeks, it’s very likely that any user personas you may have at this point are simply sets of assumptions waiting to be tested.

The point of a discovery phase is to understand better the problems users have that your product is intended to solve. You find this out by having open-ended conversations with users, observing them experiencing the problem in context and seeing the trends that start to emerge.

A user persona should be a generalisation of a group of users who share common characteristics, behaviours and goals. Only when you begin to see these trends emerging from your user research can you start to distill these general attributes into user personas. This is why you can’t start writing them at the very beginning of the process – you simply don’t know enough yet to make your user personas reflect your actual users.

2. Irrelevant backstory

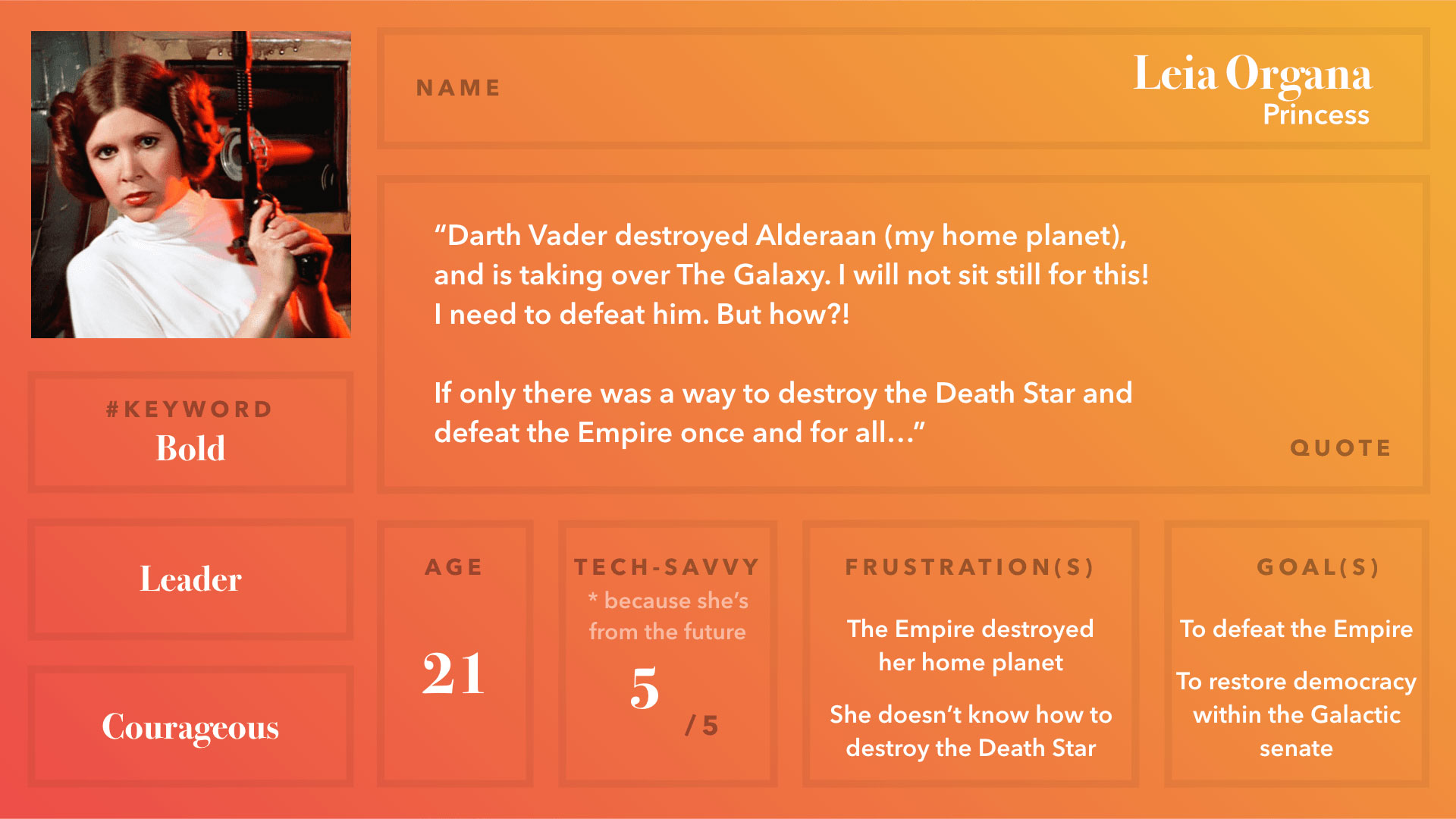

As a little test, ask people on your team to describe what a user persona is and what information it typically includes. More often than not, you’ll probably hear something along the lines of “descriptions of our different types of user, with a picture, a little backstory, their age and other demographics, hobbies and interests, IT literacy,” and so on.

Disappointingly, most of this information is irrelevant.

Think about it this way: would knowing that your typical user is a keen golfer make any tangible difference to how you build your product (assuming it’s not a golf app1)?

How would your design change knowing your users are in their thirties rather than their forties?

Would your product’s user interface differ markedly for people of different genders?

To generalise, the backstory in most user personas tends to be throwaway filler with perhaps a couple of useful nuggets of information that will genuinely have a direct bearing on your design and implementation choices.

It’s not a massive surprise that so many user personas end up looking like this. There are, after all, many templates out there that will push you in this direction.

Early on in discovery there are so many unknowns that you may not yet know what questions relevant to your product you should be asking. It’s understandably tempting to focus on demographics and interests because it’s easier and safer territory for both the interviewer and the user. Having at least some tangible answers to your questions can make you feel like you’re making useful progress (you’re not), and can lend an air of authority to your user personas, particularly if your organisation favours surveying your users over face-to-face conversations.2

So how should you make best use of your valuable face-to-face time with your users?

Concentrate on finding out information that is more likely to be relevant to your product. Focus on how users currently experience and solve the problem your product is meant to be solving.

Products are just a means to an end for users, so understand what they’re ultimately trying to achieve, rather than what the products they use allow them to do. By asking about this, you’ll start to uncover the common characteristics and goals that will allow you to craft user personas.

3. Conflating user personas and marketing profiles

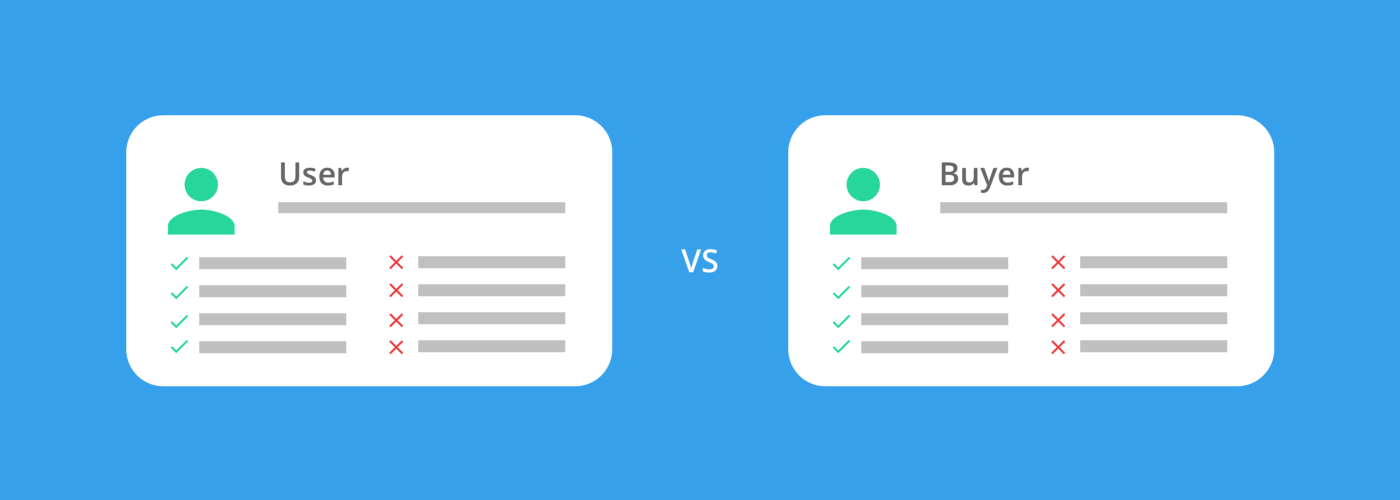

Another common mistake is when people conflate the user personas with marketing profiles. While superficially these may both seem to be about understanding the user better, there are a few key differences.

User personas are about understanding user needs and challenges around a particular task, and then grouping together users with similar characteristics, behaviours and goals into generalised archetypes. Marketing profiles tend to focus on what different groups of buyers value most in a product, and how best to engage with them to sell them the product. The difference here is between the needs of users and buyers.

Sometimes, the user and buyer are the same person, but even then, they’re wearing different metaphorical hats. A product that is super-fun and easy to use (ticks the user personas’s boxes), but which slurps up all your private data and sells it, probably won’t be bought by a privacy-conscious consumer (doesn’t satisfy the buyer persona’s needs).

Think about timing also. In discovery, you don’t yet have a clear idea of what problems you’re trying to solve or what the product will be, so it’s too early to start thinking about what people will value most when deciding to buy it.

It’s best to keep user and buyer personas separate, which means the questioning for them should ideally be done separately also.

4. Too specific and too many

As you get into your user research, you’ll possibly fall into the trap of making your user personas too specific, with the result that you end up with dozens of different personas. Trying to group users by job title rather than their shared characteristics, behaviours and goals can sometimes cause a similar effect.

If some administrators only do task X and others only do task Y, then you’re probably looking at two distinct user personas, rather than just one for ‘administrator’.

On the one hand, it may be the case that there are detailed nuances in behaviour that justify keeping user personas distinct from each other, but on the other hand, having too many will become unmanageable and unusable.

To begin with, aim to have no more than five or six user personas, with one you designate as your most important user. If this means you need to generalise a little more to keep user personas grouped together, that’s fine. It’s also fine if you need to actively defer thinking about particular niche groups of users.

To begin with, your product should be solving the biggest, most obvious user problems. Once these are out of the way, you can look at solving more niche problems, which in turn may mean you need to subdivide your user personas (based on your ongoing user research) to represent more specific groups of users.

Working in this way means you can use your user personas very effectively to focus the scope of what you’re going to release. Every release should solve at least one problem for a single user persona completely – because nobody wants a bridge that stops halfway across. That means the group of users represented by that user persona will be able to complete all the steps required to achieve a particular goal that matters to them. This way you can ensure that each product release is of value to at least one specific group of users.

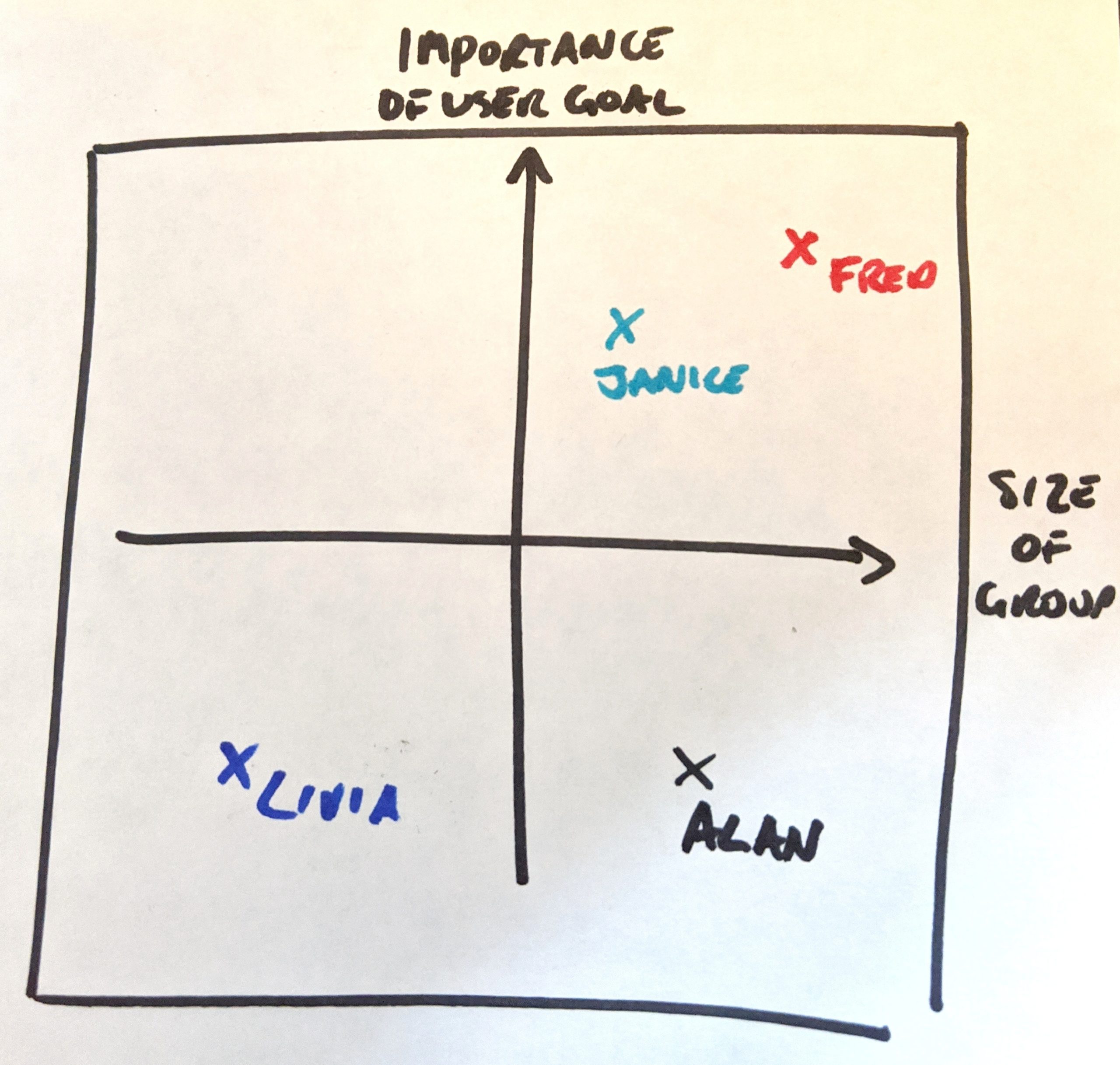

If you’re finding it difficult to prioritise your top five or six user personas, think about them in a few different ways depending on your priorities for the product release, such as:

- Size of group of user

- Frequency of their usage

- Importance of the user goal to the user

- Value of the users to your organisation

- Relative complexity of the user problem to solve

As an example, if you were primarily bothered about delivering the most value to the largest group of users, you would score your user personas by size of user group and importance of the user goal (a 2×2 grid will help here) and designate your main user persona the one that was furthest to the top-right.

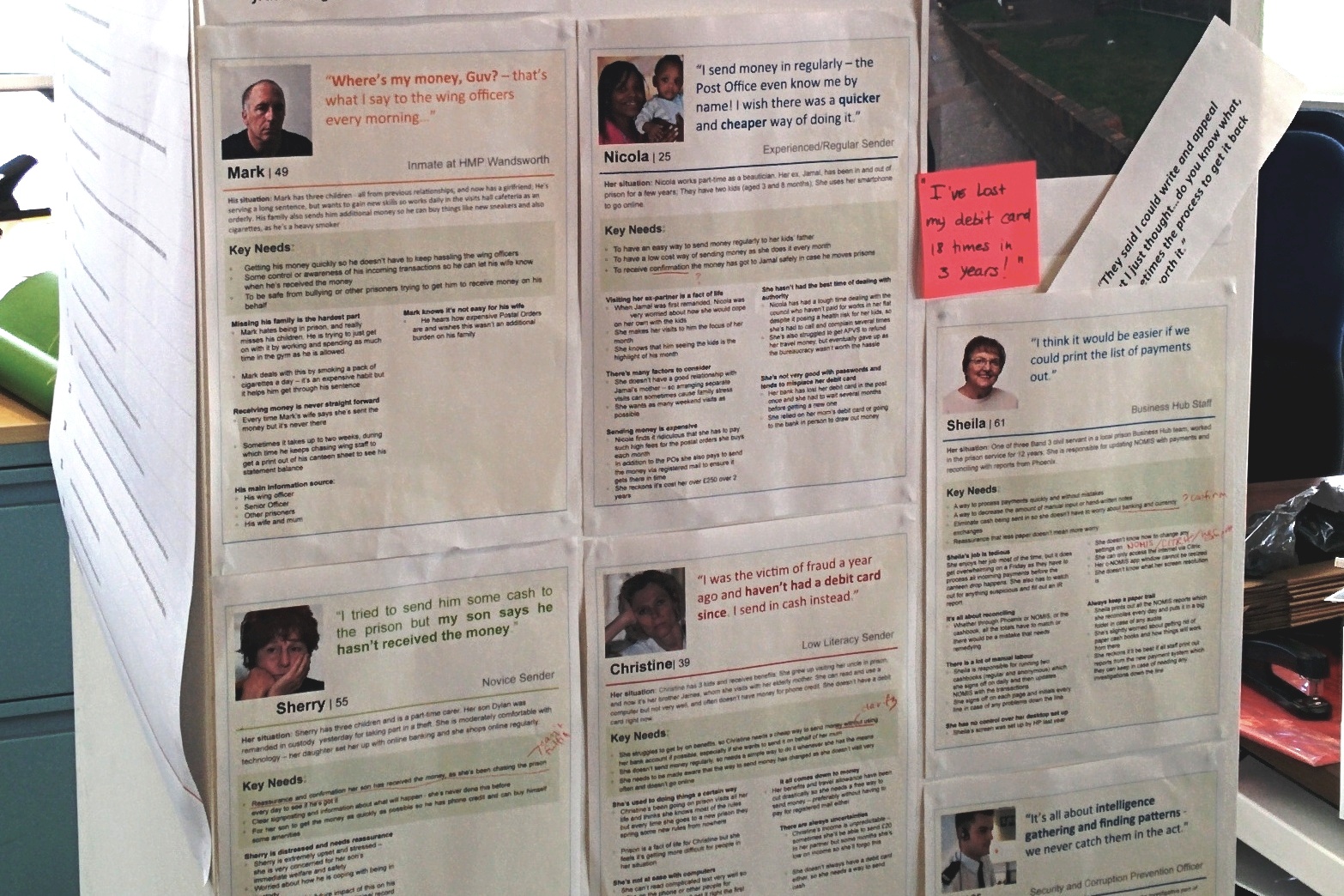

They’re a reminder of research

User personas emerge from your user research and become more accurate as you learn more and update them. They never stand still. They should always be a reminder of the user research you’ve done and the user emotions you’ve observed.

Perhaps a user persona reminds you of one memorable user who embodies the archetype for their group of users, or perhaps it reminds you of lots of people you’ve met. Either way, user personas should themselves be brief, but should always remind you of the user research you have documented in more detail elsewhere.

Leave a Reply