76: Manage the whole product

I’m writing about 100 things I’ve learned the hard way about product management. You can catch up on the previous entries if you like.

A whole product is often a complex combination of several products and services. Some you create yourself, some are created by others. You’re responsible for the whole lot, even if they’re not all directly in your control.

In this article #

It’s relatively straightforward to describe the problem a taxi service is solving. It provides a way for people (and their stuff) to get from A to B, who don’t have access to a vehicle of their own, and who want to travel at a time convenient to them.

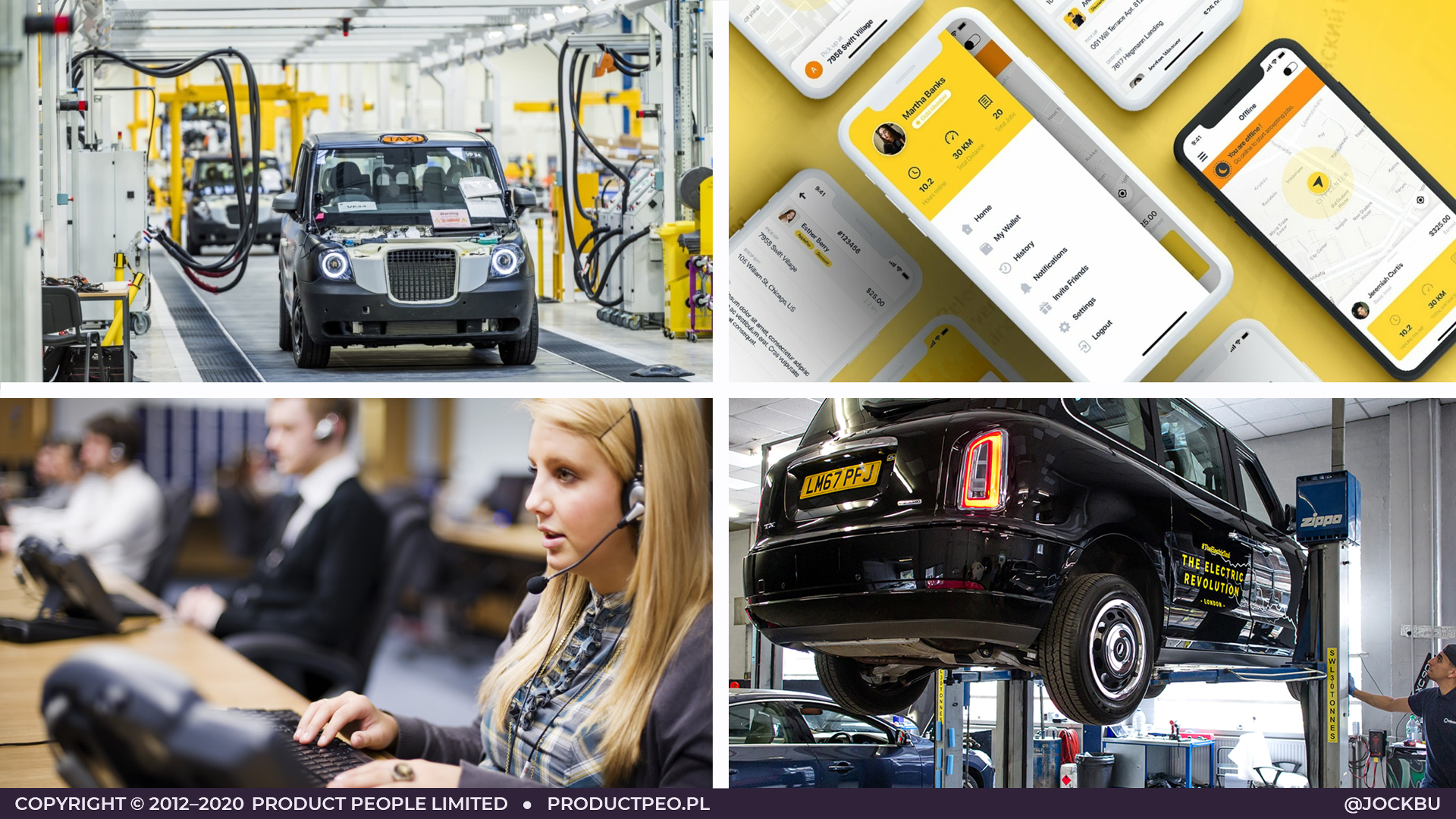

Describing what would need to go into a taxi service to solve that problem is a little more complex. You’d need (at the very least):

- a fleet of taxis, which themselves are complex products made up of many components;

- a service to maintain them, either which you provide in-house or outsource;

- some way for people to order taxis, either by phone, so you would need a call centre service, or by a ride-hailing app; and

- a way of distributing a pick-up to the nearest available taxi to the customer.

There’s inherent complexity in the detail of each constituent component that makes up a taxi service, and that’s before you consider the work needed to bring these disparate elements together into a coherent whole.

Understand how your product fits into the bigger picture

If you’re a product manager, it’s your job to get into the detail of the product you manage. Imagine you were the product manager for the ride-hailing app in the example above. You’d need to understand how, why, where, when and which people hail a cab. But to make sure your app was truly meeting its users’ needs, you’d also need a reasonable understanding of the overarching taxi service and how your app fits in with all the other products and services.

In other words, you need to think about the needs of the people directly using your product, as well as the needs and constraints of the ecosystem (the taxi service) your product fits into.

That’s one way you need to look beyond the boundaries of your product.

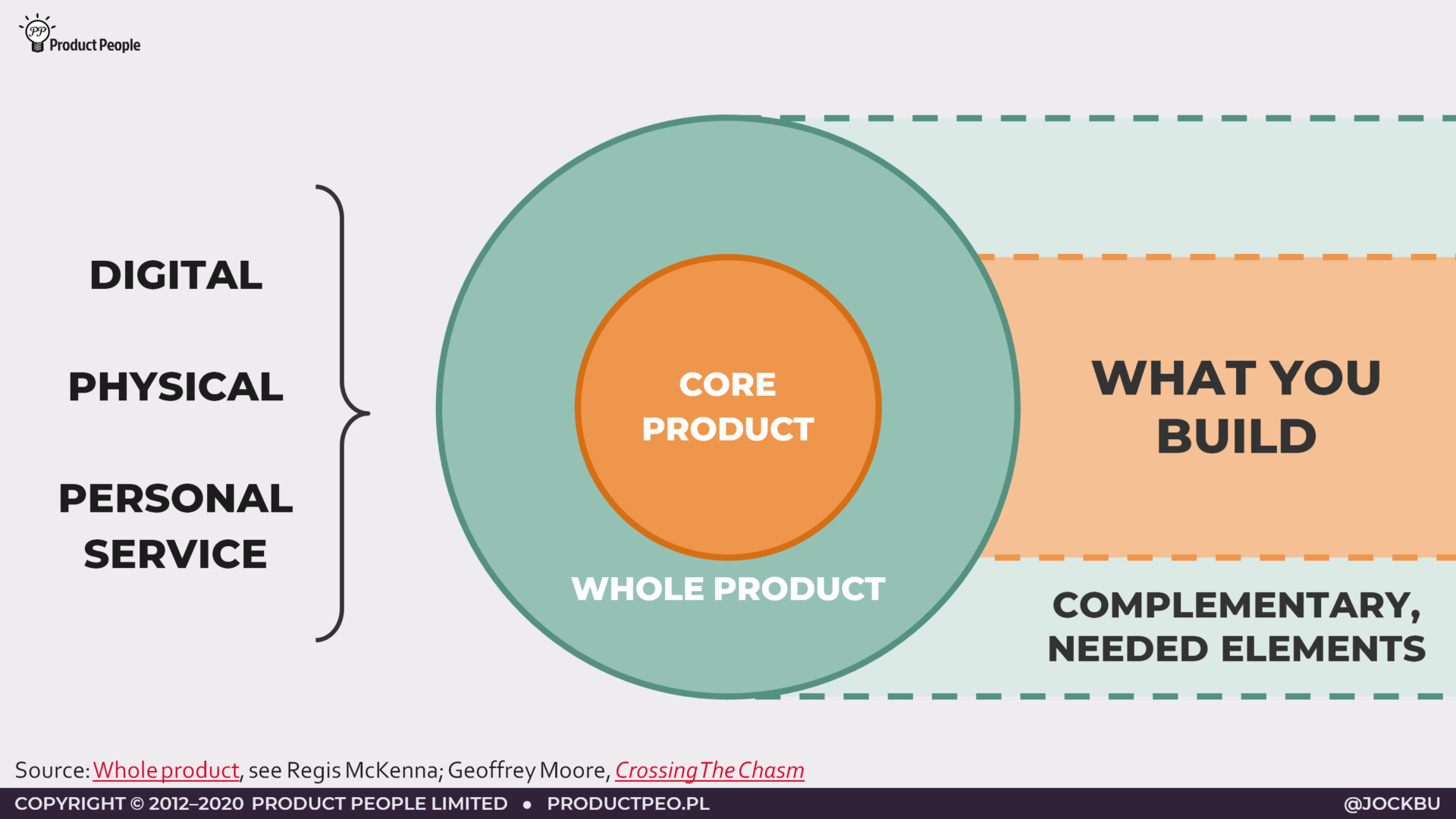

Core product versus whole product

Another time you look beyond your product is when your product’s value can only be unlocked by complementary products and services that are not necessarily in your direct control.

Take your smartphone as an example. The product manager responsible for it would have considered the various factors that would make it attractive to its target market: screen size and resolution, size, weight, processing power, memory, storage, battery life, camera and so on.

But the phone by itself can’t really do much. You still need a SIM card (or eSIM), a contract, mobile data or wifi, and apps to really unlock the value of the smartphone.

As a product manager, you’re responsible primarily for the core product you build, whether it’s a ride-hailing app, or a smartphone, or something else entirely. You’re also responsible for making sure that your product has the complementary products and services that will make it a compelling proposition to its users.

You’re responsible for the whole product, a concept first introduced by Regis McKenna, and popularised by Geoffrey A. Moore in his book Crossing The Chasm.

What do Google, Tesla and Apple have in common with the Michelin Guide?

Survivorship bias aside, the companies that seem to attract the highest valuations are the ones that not only create a successful core product to begin with, but also ensure that they form the right partnerships to make the whole product work. Over time, you’ll notice that they start to bring in-house (through upskilling or acquisition) increasing numbers of the complementary products and services surrounding their core product.

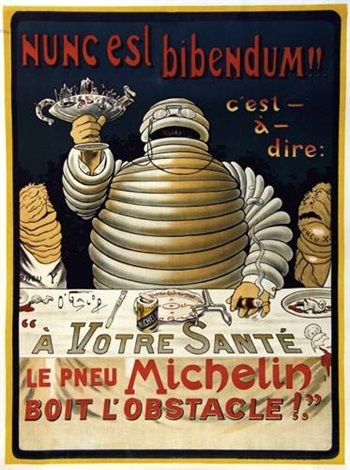

Drive to restaurants. Buy more tyres.

So the story goes, the Michelin brothers were making car tyres at the beginning of the 20th century when there were only about 2,200 cars in France and driving was seen as still a bit of a novelty pastime. They started their now-famous Michelin Guide as a way of encouraging more people to drive to restaurants, and in so doing, generate more demand for their tyre business. The rest, as they say, is history.

Controlling the ecosystem to bring more people to their core product

In Google’s case, while the search engine was the starting point, the real core product arguably was and remains the advertising engine, which followed very shortly after. To unlock the value of their advertising engine to advertisers, Sergey Brin and Larry Page first needed to have an effective and reliable internet search engine, that delivered relevant results to sufficient numbers of users, who in turn would see the adverts.

It’s doubtful whether Brin and Page initially wanted their search engine to underpin an advertising business in that way, but they were certainly thinking about it.1 Many of the myriad products Google went on to create or acquire, from Gmail to Chrome to Android and so on, served one or more of the following purposes:

- to expand its footprint in the ‘whole product’ ecosystem; in turn

- providing more opportunities for Google to advertise or learn about user behaviour to make better adverts;

- to bring more users online and more often, in order to increase the audience for their advertising.

Reducing reliance on third-parties for their whole product

Or take the example of Tesla, currently the world’s most valuable car maker, despite only having a fraction of the production output of its competitors.2 The mistake is to think of Tesla solely as manufacturer of electric vehicles (EVs). From as early on as was practical, Tesla set out to create the supporting infrastructure that would be needed to make EVs not just a practical choice for consumers, but an attractive one.

The two main complementary products needed to unlock the value of their cars? Batteries and charging infrastructure.3 Imagine if Henry Ford had decided not just to pioneer mass production techniques on cars, but had also set out to own the gas stations and oil production facilities.

Apple chips. Mmmmmm

To take another example, look at Apple’s announcement earlier this year that they were moving all their products to processors they were now fabricating in-house.4 This approach works especially well for Apple given it had been designing its own chips anyway, but had previously been outsourcing the fabrication, and given it has a valuable (and unique?) perpetual license to ARM’s Instruction Set Architecture.5

Little by little, successful companies take more and more control over the complementary products and services that unlock the value of their core product.

Build, buy, partner

We don’t all work for companies with the spending power of Alphabet (Google’s parent company), Tesla or Apple. So when you’re looking at your core product and whole product, think about what technology makes most sense for you to build yourself, what makes most sense to bring in or acquire, and which organisations you’ll need to partner with to ensure you can deliver on the whole product.

The only things you should build yourself are technologies:

- you can realistically do better, quicker, more cheaply in-house than sourcing externally; or

- only you can create, which differentiate your product from other similar ones.

The technologies you source externally are things that are better quality, more quickly/easily obtained, and cheaper than trying to do it yourself. This should be your default at least to begin with.

Own your ecosystem

Just remember the concept of the whole product when evaluating what new skills and differentiators you could be bringing in-house. You shouldn’t reinvent the wheel for its own sake. But if you’re heavily dependent on someone else’s technology to unlock the value of your own, at some point you’re going to have to evaluate whether you want to retain the dependency and associated risk, or whether you want to break free. Little by little you could be innovating and taking ownership of not just the market space your core product occupies, but the whole ecosystem your whole product inhabits.

Notes #

- Appendix A: Advertising and Mixed Motives from “The Anatomy of a Large-Scale Hypertextual Web Search Engine“, Sergey Brin and Lawrence Page, November 1997 (retrieved 19 October 2020) ↩

- “Tesla overtakes Toyota to become world’s most valuable carmaker“, BBC News, 1 July 2020 (retrieved 19 October 2020) ↩

- “How Tesla came to dominate the secret sauce of electric cars“, Mike Brown, Inverse, 24 February 2020 (retrieved 19 October 2020) ↩

- “Apple announces Mac transition to Apple silicon“, Apple, 22 June 2020 (retrieved 19 October 2020) ↩

- “Nvidia’s Integration Dreams“, Ben Thompson, Stratechery, 15 September 2020 (retrieved 19 October 2020) ↩

Leave a Reply