80: The neverending quest for product-market fit

I’m writing about 100 things I’ve learned the hard way about product management. You can catch up on the previous entries if you like.

Often the biggest barrier to your product’s widespread adoption is going to be whether it reaches product-market fit early on. Even if you do, you’re wrong if you think you never need to worry about product-market fit again.

In this article #

- Introduction

- Do you have a market?

- What is product-market fit?

- So what does he mean by that?

- Crossing the chasm

- Why is there a chasm in the first place?

- Finding product-market fit is not a one-off exercise

- Evolving needs of an emerging segment

- A timeless classic or yesterday’s news?

- Don’t kill the cash cow

- Finding product-market fit all over again

- Final thoughts

Do you have a market?

Having a market means there’s a large enough group of people who share the same problems. In other words, the problem is pervasive enough. But that’s not enough: that group of people also needs to be willing to pay someone to solve it for them. The solution has to be valuable to the people with the problem.

You can almost think of the problem as being a bit like a jigsaw with a missing piece. It has specific characteristics, like size, shape and context. Your product is potentially the solution to that problem and, like a jigsaw piece, it has to fit neatly with the characteristics of the problem.

What is product-market fit?

Venture capital investor Marc Andresssen first made his millions from Netscape, one of the original web browsers. One of his oft-repeated quotes is his description of product-market fit.

The #1 company-killer is lack of market.

In a great market — a market with lots of real potential customers — the market pulls product out of the startup.

Marc Andreessen

So what does he mean by that?

Real potential customers — for a market to be viable for your product, it has to contain people who would actually buy your product.

The market pulls the product out of the startup — on seeing how well your product meets their needs, users demand you sell them your product, rather than you having convince them to buy it.

Here’s another way of describing product-market fit: once people have seen how well your product solves their problem, they just can’t go back to their old way of doing things without feeling a little bit disappointed.

I’ve lost track of the number of companies I’ve seen which just assume that everyone will want to buy their product purely on the strength of it existing — a bit like the premise of the film, The Field of Dreams. (Those companies were all terribly, terribly wrong, by the way.)

To truly achieve product-market fit, you need to have the combination of both a product and business model (how you engage with the market) that together meet the needs of customers. You can read more about discovery in another of my posts.

Crossing the chasm

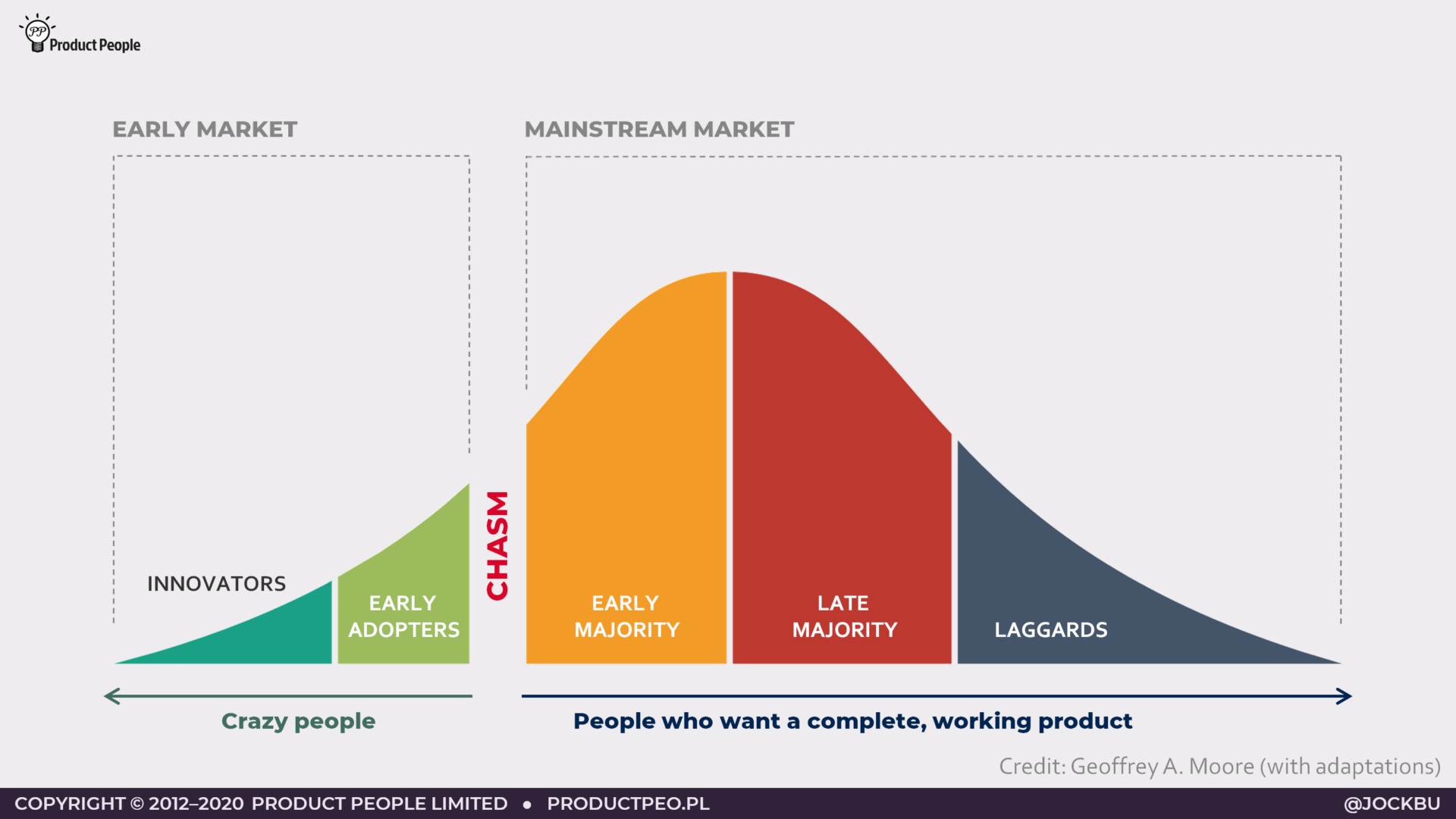

If you’ve ever read Geoffrey Moore’s book, Crossing the Chasm, there is a gap you need to bridge separating the relatively small numbers of early adopters from the much larger majority of mainstream potential customers. Product-market fit is a bit like the bridge that allows you to cross that chasm.

Why is there a chasm in the first place?

It’s because the needs of innovators and early adopters (or “crazy people”) are different to those of the mainstream majority. Crazy people are happy to take an early product either because they just love to be on the cutting — or bleeding — edge of technology, or because they see the potential of a new technology and are willing to accept some flaws in your product early on to steal an advantage from their slower-moving competitors.

If you want to get into the mainstream market you first have to figure out the differing problems and needs of this different group of people. This is why finding product-market fit is so challenging.

To begin with you might feel as though you’ve achieved product-market fit, particularly if you’ve got a handful of crazy people who are already using your half-baked product like borderline obsessives and think it’s fabulous. The problem is that they’re not the segment of the market you want. There’s simply just not enough of them to sustain your business model. So to get into the mainstream market you effectively have to find product-market fit all over again.

Many of the organisations I’ve worked with had been running with a product for ages and yet they still hadn’t achieved product-market fit for the mainstream. They were continually struggling to get people to adopt their product and usually burning through advertising cash in the process, instead of spending their time and money figuring out what product-market fit would look like. Many products never manage to find it.

Finding product-market fit is not a one-off exercise

The thing is that finding product-market fit isn’t a one-and-done exercise as the single chasm would suggest. It’s really more of a moving target that you need to keep reevaluating over the entire product lifecycle.

The good news is that, unless you’ve stopped doing user research completely (Pro tip: don’t stop) or unless the market has taken another hard left due to a global event like COVID-19, you should be able use your ongoing user research to track the incremental market moves relatively easily and adjust your product as it matures accordingly to maintain product-market fit.

Evolving needs of an emerging segment

Matters become a little bit more complicated when what you’re seeing is actually the emergence of different sets of users with differing needs. As your product matures, there might be a sub-group in your late majority users who largely just want your product to stay the same because they’re averse to change and prefer familiarity. This sub-group goes on to become your laggards (or sceptics).

However, another emerging sub-group of users within the late majority may be more tolerant or supportive of change, and who would prefer your product to evolve in line with their own changing needs. This is probably when you need to start thinking about a couple of potential product strategies.

A timeless classic or yesterday’s news?

You might want to split your product into a “classic” version that maintains the legacy features as they are for the laggards (the people who want the product to stay the same), and a separate, new product that leaves the legacy features behind and supports the evolving needs of this new, emerging early majority of the market.

Some organisations make this transition at a major product version change by deprecating legacy features and effectively stranding laggards on the previous major version. Others take the approach of creating a separately branded product.

The approach you choose all really depends on the relative value, size and stubbornness of your user segments. Your choice of strategy is also going to depend on other factors, such as how easily you’ll be able to migrate users from your legacy product onto the new one when the time comes to retire it.

Don’t kill the cash cow

If you have loads of users on a cash-cow product, but they’re mostly laggards, then there’s no point in throwing away the revenue that they contribute by forcing an unpopular upgrade. Instead you should keep maintaining (but not actively developing) that product for the people who don’t want it to change, and invest the majority of your engineering time into a new, separate product.

Conversely, if even your laggards are willing to contemplate an upgrade, just not for a long time, then you might want to consider the major version approach, coupled with a long-term support option to keep your laggards happy.

Finding product-market fit all over again

What many organisations don’t realise is that when they reach this stage and there’s a new market emerging from the laggards, they actually have to find product-market fit all over again for each of these two distinct groups.

Finding product-market fit is something you need to reevaluate every time the characteristics and needs of your users evolve. As this is happening continually and it’s difficult to perceive that shift as it happens, you need to keep up with your user research and frequent release cadence so that your product can seamlessly track along with your users’ evolving needs.

Leave a Reply