PRODUCTHEAD: A quick overview of discovery

PRODUCTHEAD is a regular newsletter of product management goodness,

curated by Jock Busuttil.

true product managers wait #

every PRODUCTHEAD edition is online for you to refer back to

tl;dr

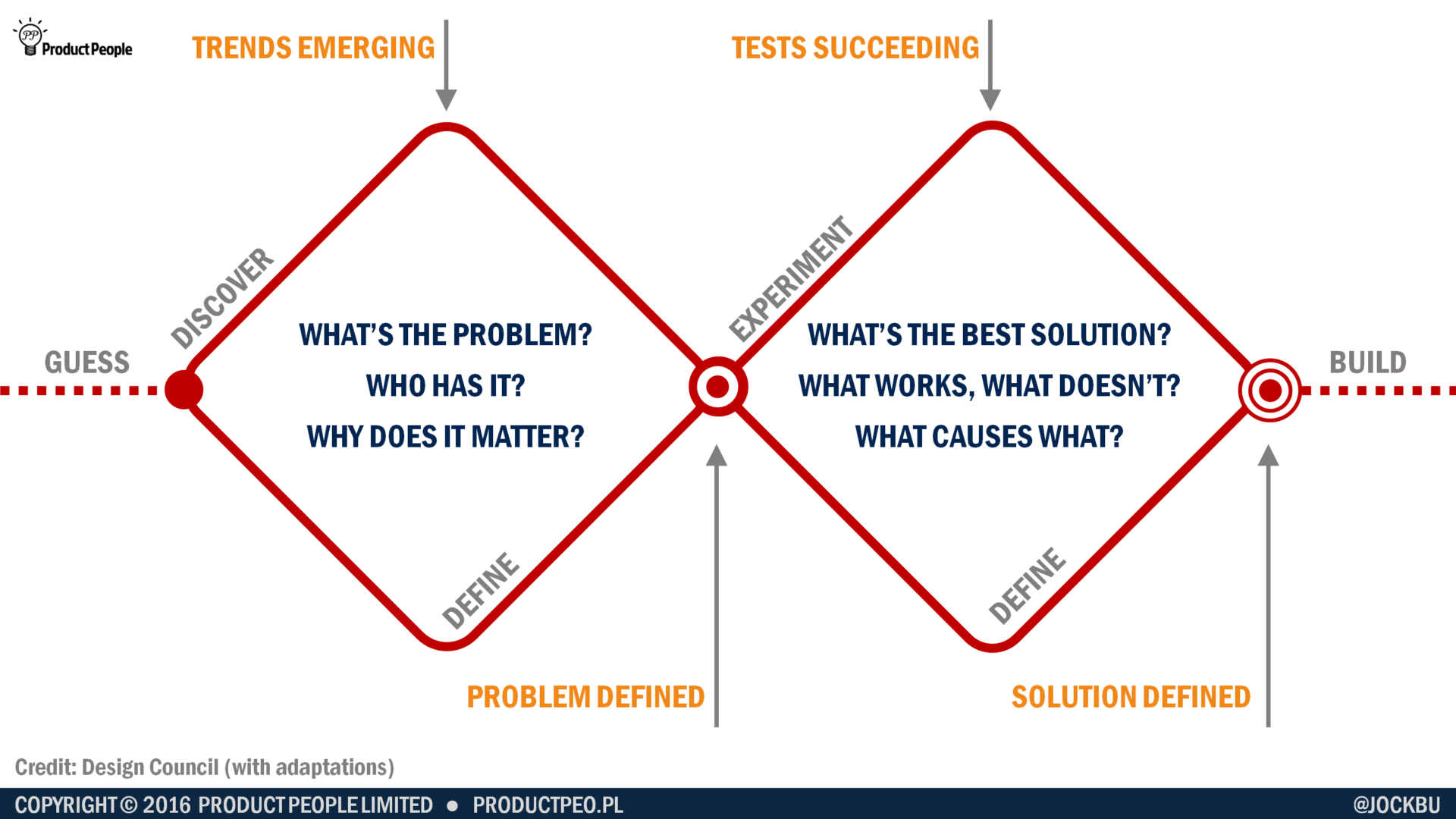

Have a bias to test, learn, and to put code in production

Feed what you learn from exploring solutions back into your understanding of the problem

Help stakeholders visualise their ideas to make them easier to challenge, assess risk and test out

hello

Last week I wrote up a quick overview of discovery for a client recently with links to lots of useful further reading. I thought you might appreciate it also.

If you don’t already have a copy, as always I would recommend reading Erika Hall’s Just Enough Research for practical advice for product people running user research on tight budgets.

1. Goal of discovery #

On a continual basis

to identify likely candidates of

real, urgent, pervasive and valuable

user problems / needs / opportunities

for further investigation

and to discard the ones that are not.

2. Identifying a single opportunity for discovery #

Sometimes you don’t have a single, specific area you’d like to investigate in your discovery. This could be a variety of reasons, such as an overly generous mandate (“find our next product”) or input from several stakeholders who all have their areas of interest.

When you’re in this kind of situation and don’t know where to start, to begin with I would suggest you need to receive permission and budget to do a few initial explorations. Scott Colfer has a good article on these explorations you do prior to starting discovery proper.

This looks like:

Identifying a short list of reasonably focused areas of potential opportunity for investigation. These would include the areas your stakeholders has expressed an interest in, as well as the areas you believe to be worthwhile from any (anecdotal) evidence you may already have.

Setting a timebox of e.g. 2-4 weeks for each exploration, with separate explorations running sequentially. The timebox lets you estimate their cost and give senior management relative certainty on timescales. You’re not doing a full discovery yet, you’re just trying to figure out which is the more worthwhile opportunity, so err on the side of shorter timeboxes.

Setting stakeholder expectations on what you would then hope to learn during exploration and what the outcome of each might be:

- worthwhile — there is evidence of valuable / pervasive / urgent need, so the next step would be a discovery to explore this single opportunity in more detail

- not worthwhile — there is evidence that there is no opportunity, so stop there and move onto next area on the short list

- undecided — insufficient evidence either way, so park this for later and review the other areas on the short list to see if there are better opportunities to pursue

You would present back your findings to the senior management team after each exploration, along with your recommendation on what to do next.

This hopefully puts you in the position to assess the merits of different potential areas based on evidence, and to park ideas (from any source) that don’t translate to any observable opportunity.

It is entirely possible that none of the areas on your initial shortlist results in further action. This is still a success as it avoids the future costs of a detailed discovery and attempting to develop a solution that will never gain traction in the market. However, it is useful to set expectations with stakeholders as not everyone will view such a result as positively.

3. Planning and running the discovery #

From your short list, you’ve decided on one specific opportunity to explore in more detail. This is where you start the discovery proper. Again, being a discovery means it is not guaranteed to run through to prototyping solutions and eventually building a product. You may learn things during discovery that make the opportunity far less attractive. And again, stopping at this point is a successful outcome.

Have a read / watch of the edition of PRODUCTHEAD below. Erika Hall and Steve Portigal offer some really valuable and practical advice for planning and running discovery for product people:

PRODUCTHEAD: How to plan a user research interview

In particular, from Steve Portigal:

Business question: What challenge does the business face?*

Research objective: What do we hope to learn to help us answer that business question?

Participant questions: What questions can we ask customers to help us achieve that research objective?

* Using the ’five whys’ or Randy Silver’s Dragon Mapping may help to draw this out if unclear.

I’ve also written plenty about what running a discovery looks like, so rather than repeat it here, take a look at:

PRODUCTHEAD: (Re)discovering discovery

Find the tipping point in your user research

PRODUCTHEAD: How product teams can measure discovery

4. Analysing your results #

Discovery is very much qualitative research. Our questions are simply not specific enough to use quantitative techniques yet. See this technique cheat sheet and this summary of which techniques to use when from Nielsen Norman Group.

You may need to do some thematic analysis (= affinity mapping) to help draw out the common themes from your research.

We’re looking for clear signal. This could be as basic as evidence that more than half of the people you spoke to (comparable, representative users) experience the same problem or need and that it would be valuable to them to solve it.

You might then iterate by asking how the people with the same need are similar, and how the people without the problem differ. This then allows you to refine your definition of the target user. Then you can go back again and validate your understanding by targeting only the profile of the people you expect to have the problem. This time you can set the bar higher, perhaps expecting 80% of interviewees (for example) to have the problem you describe.

Positive feedback should give you the confidence to continue investigating, although it still doesn’t guarantee you’ll actually find true product-market fit later on.

5. Deciding what to do next #

Even though you’re running your discovery on a single area of interest, you may find that several promising opportunities emerge. You probably won’t have the capacity to do all of them at the same time, so you need some way to evaluate which are going to be better candidates to pursue.

Each time we uncover multiple areas of interest, we do the same thing: evaluate their relative merits (for the user and for the organisation) and focus in on one or two of them. We’re always trying to avoid spreading ourselves too thinly and doing a lot of things badly, rather than one thing well.

The following edition of PRODUCTHEAD has some further suggestions for techniques to evaluate potential opportunities in a systematic way:

PRODUCTHEAD: How to evaluate product opportunities

You could then start prototyping possible solutions for the most worthwhile opportunity you’ve identified.

PRODUCTHEAD: Exploring the solution space with prototyping

Speak to you soon,

Jock

what to think about this week

The discovery illness

When helping teams and companies shift towards the product model, one of the key concepts introduced is practicing product discovery.

In this article, I’ll surface a common anti-pattern that teams stumble upon when having the opportunity to work more with product discovery: the Discovery Illness.

“Can we make it smaller? How can we test it?”

[Marcus Castenfors / Crisp]

Alpha is discovery

The problem with moving fast in a discovery, when you’re exploring a new problem domain or trying to validate a hypothesised solution, is that many things are uncertain. You’re working in the Great Unknown and it’s hard to get your bearings: when will we be done? what do we know and not know? have we made any progress? are we even in the right place?

[Steve Messer / Harsh Browns]

It’s okay to start with a stakeholder’s solution. Just don’t stop there

It doesn’t matter if you’re working in a complex organisation or not. It’s pretty common to work on projects where you have opinionated colleagues who have a “stake” in the product or feature working. Either to their part of an organisation or their reputation.

This can be the starting point for a lot of terrible features and ideas. Or things that sound very believable but aren’t quite right. Particularly if teams just get their heads down and do the thing they’re asked.

But this doesn’t mean they don’t understand things or their vision is invalid. Or not a starting point to use.

[Andrew Duckworth]

recent posts

Moving up to a CPO or VP Product role

Stepping up to a Chief Product Officer (CPO) or VP Product role doesn’t so much change what you do. Rather it amplifies everything. This guide lets you know what to expect.

Liberating and terrifying in equal measure

[I Manage Products]

I want to update my pricing strategy. Where do I start?

“My product currently has one tier of per-seat pricing for all customers. I want to change my pricing strategy to cater differently for SMEs and enterprise customers. Where do I start?”

A few pricing concepts to consider + further reading

[I Manage Products]

How do I make my product roadmap a better communication tool?

“My product roadmap is not getting the right information across to other people in my company. In particular, my customer success and marketing teams are struggling to plan their work for upcoming product releases. I’m also not sure how I can show my roadmap’s relationship to the half-yearly OKRs we set. How can I improve it?”

Your product roadmap is a communication tool

[I Manage Products]

can we help you?

Product People is a product management services company. We can help you through consultancy, training and coaching. Just contact us if you need our help!

Helping people build better products, more successfully, since 2012.

PRODUCTHEAD is a newsletter for product people of all varieties, and is lovingly crafted from the rabbit hole of self-publishing.

The different question types come from the second edition of my book, Interviewing Users, available here:

https://rosenfeldmedia.com/books/interviewing-users-second-edition/