Should a growth product manager even be a thing?

There’s an ongoing debate about generalist product managers versus emerging product manager specialisms (such as ‘growth product manager’). I think there is room in our profession for both. Let me explain.

In this article #

- Introduction

- “No one wants to get rich slow”

- The rise of the growth hacker

- And so to growth product managers

- A repeating cycle

- Experience is lumpy

- Beware ‘lack of experience’ rebranded as ‘specialism’

- Different dimensions of experience

- Where to start: be honest about your skill gaps

- Build out your experience

- Final thoughts

- Further reading

“No one wants to get rich slow”

Airbnb CEO Brian Chesky once asked Jeff Bezos what was the best advice he’d ever received from Warren Buffett, who was sitting next to him. Bezos replied by telling how he’d once asked Buffett why more people didn’t copy Buffett’s investing approach. Buffett replied, “Because no one wants to get rich slow.”

Most technology companies live and die by their ability to transition successfully and rapidly from a startup to a scale-up. This is the famous chasm that Geoffrey A. Moore refers to in his book, Crossing The Chasm. The success of their long-term business model is often predicated on having a large enough paying customer base to:

- offset the financial debt incurred before reaching the point of being able to provide a viable paid-for service to customers (i.e. all the research, development and people costs they incur on the way to product-market fit);

- benefit from the economies of scale, where revenue is growing more quickly than the cost of providing service to users, so each user becomes increasingly profitable as the paying user base grows;

- subsidise both incremental development of the original product, and research and development of the next product(s);

- attract series A (B, C) funding from investors seeking evidence of growth; and

- increase the valuation of the company prior to exit.

These last points in particular seem to fuel the desire for rapid growth. Startup founders seem to perceive the market as only able to support one dominant player, so every startup engages in this mad dash to acquire market share as rapidly as possible. In his book, The 7 Habits Of Effective People, Stephen R. Covey refers to this as a ‘scarcity mindset’.

Growth is important, for sure, but not every company needs to grow at breakneck pace. There’s usually plenty of market to go around (in Covey’s terms, an ‘abundance mentality’), and some companies are perfectly content with a smaller, more stable and slower-growing customer base.

But as Buffett observed to Jeff Bezos, “no one wants to get rich slow,” which is why growth in particular seems to be priority of startups and their investors.

The rise of the growth hacker

You probably remember Dropbox’s hugely successful and oft-copied referral scheme that rewarded both the referrer and the referee with additional free storage on the file-sharing service. It’s 2010 and Sean Ellis, who oversaw Dropbox’s viral growth campaign, coins the phrase ‘growth hacker’.

Around the same time, Eric Ries has been popularising the idea of ‘growth engines’, a concept he includes in his 2011 book The Lean Startup. Companies of all sizes want what Dropbox has, creating demand for people who can make this happen. Supply turns up in the form of self-styled growth hackers, specialists who achieve this outcome for companies, with varying degrees of success, and occasionally in ways that make that growth sustainable in the longer term.

For more context, Andy Johns has a particularly insightful post-mortem on the rise and fall of growth hacking.

People spoke of growth hacking and hired for a growth hacker as if it were a panacea. Many months later they found themselves optimizing a product that consumers didn’t care for, dangerously short on cash, and with zero interested investors or buyers.

“A post-mortem on growth hacking” by Andy Johns

And so to growth product managers

You’ve probably seen the increasing numbers of job adverts for growth product managers. And you’ve probably seen some of the debate about whether the emergence of this specialism is a good or a bad thing. I think there’s room in our profession for both generalist product managers and specialists to coexist, partly because we’ve been here before.

If you’ve read this far and are still wondering what a growth product manager is defined as, take a look at this 2021 report that spells it out:

A Growth PM needs to be willing to collaborate with teams to ensure any changes they recommend to certain functions or features will bring positive results, maximize revenue and accelerate growth.

“Rise Of The Growth PM: Report 2021” by Heather James, Adam Bennet & Jon Sayer, Product-Led Alliance

In other words, once product-market fit has been truly achieved, a growth product manager specialises in making the ‘hockey stick’ user growth curve a reality. They do this by focusing their efforts on instrumenting, experimenting with, and optimising the product(s) to make this happen.

Some companies have this role working company-wide in collaboration with the generalist product managers responsible for specific products; others use the growth product manager as the sole product manager for a product.

I don’t think anyone would suggest that generalist product managers has been neglecting this aspect of their product’s life cycle. Rather, the emphasis is on using specialists to yield better results, more quickly — the implicit compromise being that other aspects of product management are de-emphasised, at least temporarily.

A repeating cycle

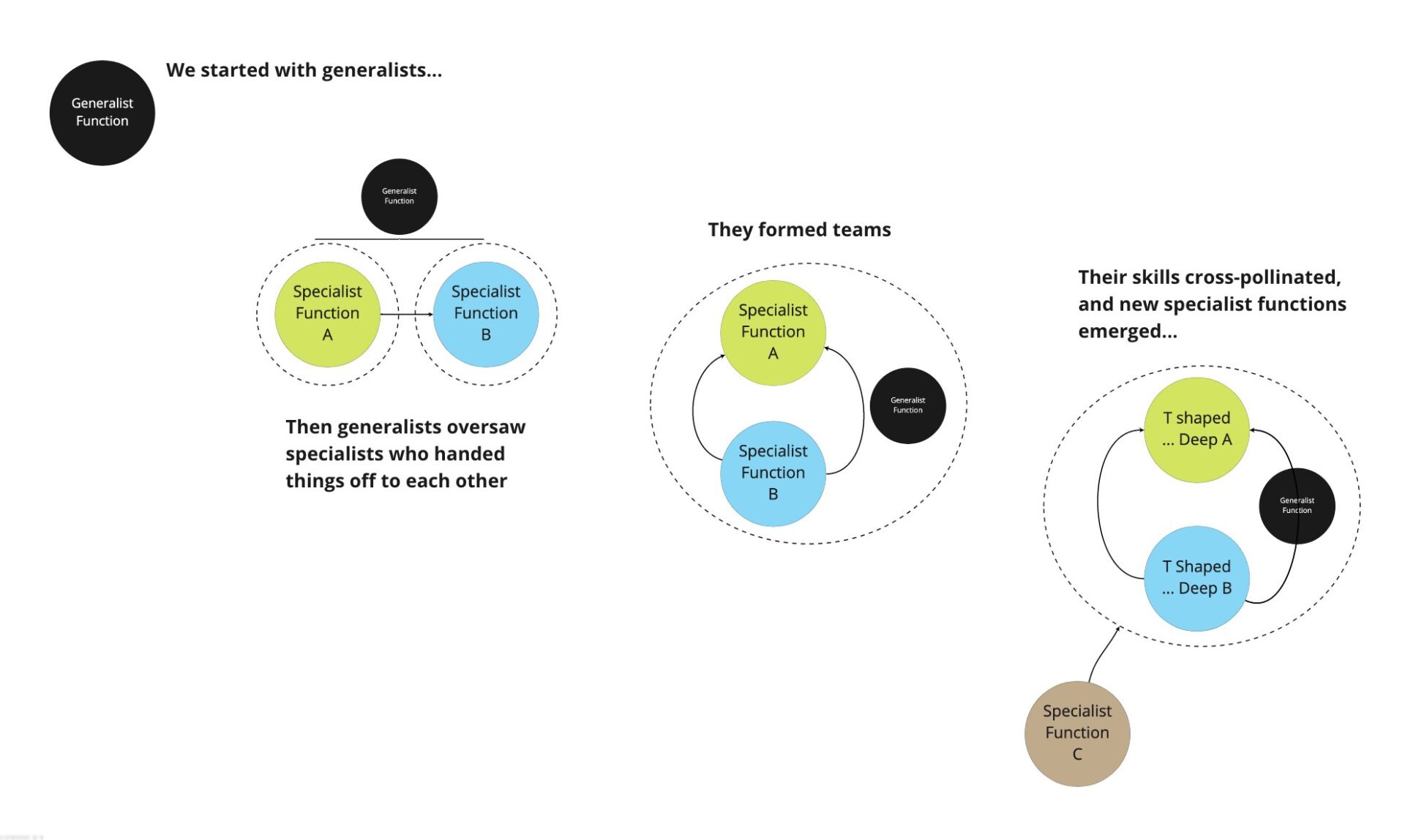

John Cutler astutely observes that the cycle of specialisms emerging from a generalist function happens over and over.

We’ve seen it happen before. Let’s take a few quick examples to illustrate the point:

generalist IT function -> infosec

developer -> front-end / back-end developer -> React / Angular specialist

And for bonus points:

front-end / back-end developer -> full-stack developer

The demand for the combination of multiple specialisms in a single role (because companies generally don’t want to pay to hire a whole new team), coupled with the ubiquity of skill availability causes a generalist function to emerge again. Notably, the new generalist function is markedly different from (and to an extent more specific than) the original generalist function it evolved from.

You can see this with the product manager function also. I’d argue it’s been through a few of these cycles already as it is cross-pollinated by skills from adjacent disciplines such as user experience and design, while shedding the process-heavy trappings that came from the world of project management.

We’re seeing this cycle being repeated explicitly with growth product managers, and to a lesser degree with discovery product managers (as noted above, everyone wants growth, but far fewer understand the value of discovery). Companies are sophisticated enough to recognise at what stage of the life cycle their product is currently, and are choosing to hire a product manager with deeper experience in the corresponding specialism.

I have a concern on specialising in a particular product life cycle stage. If you only ever manage early-stage products from ideation to product-market fit, you may be lost when it comes to managing the product through the inevitable later stages of its life cycle.

In practice, you might not stick around long enough at a company to be the same product manager that creates and retires a particular product. The side-effect of specialism by life cycle stage is that you are tied to a particular period of time for a product. Once that time has passed for that product, your skill set will no longer be in demand.

“PRODUCTHEAD – To specialise in product management?” by Jock Busuttil

Experience is lumpy

We tend to acquire product management experience unevenly — we find ourselves in situations where we suddenly have to get really good at some particular aspect of the role because that’s the most burning issue at hand.

Take the example of the delivery teams I encountered several years ago in UK government. Because they had taken several new services to market already by the time I encountered them, they were amazing at discovery, prototyping and sending live an initial product iteration. But when it came to figuring out how they would handle the ongoing support and maintenance of the services they’d created, they struggled.

This surprised me because the reverse was true for most software companies I’d worked with up until that point: they were really adept at supporting existing products, but all at sea when it came to discovery and validation for a new product.

Particularly early on in your product management career, you’ll probably have a ‘lumpy’ experience profile — lots of experience in one or two areas, much less (or none) in others.

Beware ‘lack of experience’ rebranded as ‘specialism’

For me at least, I think there’s a stark difference between people who say:

“I’ve built up my general experience in different aspects of product management, and I’ve chosen to specialise in an area I enjoy most / am best at,”

and:

“I’ve never done any of these other aspects of product management, so I’m therefore a specialist in the one or two I have experienced.”

I believe there’s a baseline spread of experience any good product manager should have. (Would you trust a doctor’s diagnosis if they’d somehow managed to avoid whole subject areas like immunology or anatomy in their medical training?)

You need to understand the fundamentals to provide context to more specialised work. If you don’t understand why a particular technique works in a given situation, you’ll find it tricky to identify seemingly similar situations where the technique definitely would not work.

Until you’ve got the fundamentals covered, I would argue that you’re not yet ready to specialise. After that point, specialise, by all means.

Different dimensions of experience

Despite how they present themselves when attracting new hires, few organisations are universally good at all aspects of product management. ‘Best practice’ is a rather fluid concept. It can vary wildly depending on whether you’re managing a brand-new product in contrast with an established, mainstream product or a product you need to decommission and replace.

Likewise, there’s nuance in the product management approach you should take depending on the maturity, culture and organisational structure of the company in which you’re working. A product manager has a very different job in a company whose senior management team ‘gets’ product management, than in one where product management is referred to as the ‘profit prevention squad’. (Yes, this actually happened to me. Some constructive tips here for doing at least some good product management when faced with this situation.)

Then there are the characteristics of the market in which your products are being sold: clear, blue ocean versus highly competed; fast-moving and risky versus slow and conservative; business-to-consumer (B2C) versus business-to-business (B2B).

With all these different dimensions to consider, it’s no wonder you hear product managers saying “it depends” so often.

Where to start: be honest about your skill gaps

Another tricky aspect is that you may not know enough about the breadth of the product management role to identify the fundamental skills you’re missing.

If that’s the case, I can help. I’ve put together a self-assessment survey that takes you through the fundamental skills of a product manager. I’ve also written about the approach if you’d like more information first.

If you take the survey, drop me an email afterwards to confirm who you are and I’ll share with you (for free) a Google doc that graphs your results against an average taken from a range of product managers. This will highlight the fundamental skills you need to work on. And of course, your survey results will remain confidential.

Then separately you can think about acquiring experience in discovery and growth, or B2B and B2C, or particular market sectors, before you decide to specialise.

Assuming you’re motivated to build out your experience, the next step is to figure out how to fill the gaps.

Build out your experience

It’s useful to know where your strengths lie, and where you need to build out your experience. Choosing to put yourself in less familiar situations is always going to be a bit uncomfortable; it disrupts your habitual ways of working, plus you’ll need to work that much harder to acquire and bed in new skills.

If you’re lucky, you may have the opportunities and mobility within your current organisation to experience products at different life cycle stages, perhaps even different markets. In most cases, you’re going to have to change jobs — more disruption — a prospect not everyone relishes.

Then of course you have the additional challenge of finding an organisation that is willing to recruit you based on your potential rather than solely on your experience. Those organisations are definitely out there (otherwise nobody would be able to break into product management), even if their job adverts aren’t great at saying so.

Final thoughts

It seems to be natural for specialisms to emerge from a generalist role in response to greater awareness of new and desirable techniques. These specialisms can grow in detail to become fully-fledged roles in their own right, perhaps fall out of fashion, or eventually merge back into the generalist role.

Whether or not we’ve been calling out these specialisms by name, such as ‘growth product manager’, each of us may have already specialised to a certain extent. Even with a solid grasp of the fundamentals of product management, we may find ourselves working exclusively with B2B products, or in a particular market sector.

Our individual career experiences in one or other dimension of product management, coupled with our reluctance to step outside of our respective comfort zones, can mean that we end up specialising to a certain extent anyway.

There’s nothing wrong with specialising. Rather the consideration is the longevity of your chosen specialism. You probably don’t want to devote a significant proportion of your career to a specialism that’s likely to fall out of fashion or become obsolete, without having a more general practice to fall back on.

Further reading

Crossing The Chasm by Geoffrey A. Moore

“The neverending quest for product-market fit” by Jock Busuttil, I Manage Products

The 7 Habits Of Effective People by Stephen R. Covey

The Lean Startup by Eric Ries

“A post-mortem on growth hacking” by Andy Johns

“Rise Of The Growth PM Report 2021” by Heather James, Adam Bennet & Jon Sayer, Product-Led Alliance

“PRODUCTHEAD – To specialise in product management?” by Jock Busuttil, I Manage Products

“The unifying principles of product management” by Jock Busuttil, I Manage Products

“Q&A: Should I take a different role before applying to become a product manager?” by Jock Busuttil, I Manage Products

“The 12 most important soft skills every product manager needs” by Jock Busuttil, I Manage Products

“The 16 most important technical skills every product manager needs” by Jock Busuttil, I Manage Products

“How to measure product manager performance” by Jock Busuttil, I Manage Products

Please note that some of these links are Amazon affiliate links, meaning I would earn a small commission on any purchases you made.

Leave a Reply